@adamk It seems to me that the writers of some optimisation software endeavour to raise the fabric temperature by ‘hot-housing’ during the TOU cheapest rate hours to reduce consumption during more expensive times of the day. This scheme does go against the grain somewhat if one has batteries to ride out the expensive times; I stopped using Homely Smart+ settings for this very reason. Hot housing to an uncomfortable level to save using energy at other times doesn’t seem sensible then. Regards, Toodles.

Toodles, heats his home with cold draughts and cooks food with magnets.

@adrian — can you expand a little, and show your actual workings, as I don't fully understand your method? Are you really using °K (Kelvin)?

Also bear in mind my house is not well insulated (it's an old listed cottage, limited scope for insulation once the obvious has been done), but it probably does have a relatively high thermal mass for its size.

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

As long standing followers of this debate will know, theoretical assessments of whether setbacks achieve savings tend to suggest the savings are modest, possibly even existent or, shock horror, setbacks actually cost more. Yet my analysis above, and similar other empirical studies, suggest the savings are not trivial. Either my experimental method is wrong, or the theory is wrong (or both are wrong...).

No one has so far suggested that a setback doesn't save money when it is actually in progress. If my heat pump is running at a steady rate using 1kWh per hour, and I turn it off for 6 hours, I will save 6kWh. The period of uncertainty instead lies after the setback, during the recovery period. In simple terms, the theoretical approaches say you have to put in extra heat, over and above what you would have used without a setback, to replace the heat lost during the setback. To get to a break even point (no net saving), given the above setback, I would need to use an extra 6kWh during the recovery period, over and above what you would have used anyway.

By way of a short diversion, I suspect the duration of the setback may matter. If you are lucky enough to go skiing for a couple of weeks, and turn off the main heating while you away, few will doubt that you save money on the heating bill. You get two weeks of savings, and only one recovery period. If you live in the country, and go up to town for the weekend, and turn the off the heating in your country home while you are in town, you are very likely to achieve a saving, two days of savings, and only one recovery period. I've got a hunch that things might start to change when the recovery period is either the same length as or longer than the setback period, which can happen with overnight setbacks.

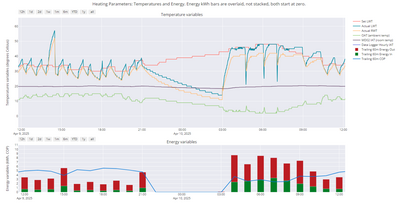

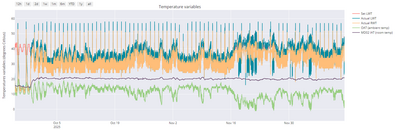

Now back to what happens during a recovery period? In my setup, my auto-adapt script may or may not kick in (the actual IAT has to be at least 1°C apart from the desired IAT, 19°C, for it to kick in). Let's look at the night of the 9/10th April, a fairly typical night from the range I looked at in my analysis in my previous post. Bear in mind the energy data in the lower chart is for the preceding hour, eg the values shown at 2100 are for the period 2000-2100:

During the setback, the IAT fell from around 20° to just over 18°C, not a big enough to trigger auto-adaption. The recovery period was about 3 hours, the IAT was back to where it should by about 0600. Now let's look at the hourly energy use during the period shown:

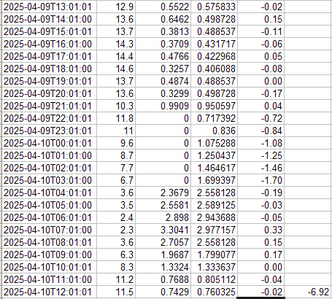

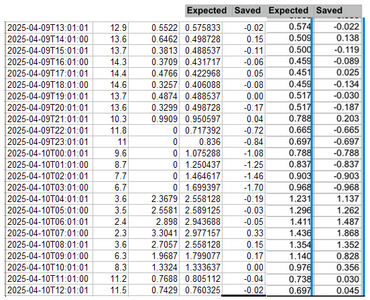

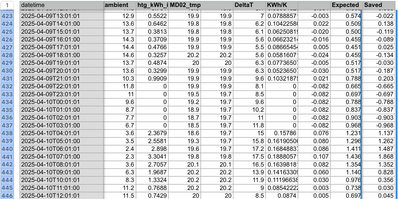

The columns are datetime, OAT, Observed, Expected, Observed - Expected, Sum of Observed - Expected (bottom right). Apparently I saved 6.92kWh that night by using a setback.

But the odd things is, there is no obvious extra energy being put back in during the recovery period. Yet the recovery certainly happens, and in good time. There is no visible extra use during the recovery period to be offset against the undoubted savings during the setback, so in effect i get the full benefit of the setback.

@jamespa — thoughts? Or anyone else?

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

@cathoderay the principle is as probably described somewhere above, that the energy usage is directly proportional to the deltaT between outside and inside temperature. As we don’t have the heat output numbers, I’m assuming a constant COP and calculate the kWh used per degree kelvin deltaT.

This can be calculated as the sum of kWh used devided by the sum of deltaTs. This gives a number of 0.082kwh/K. Then I create a new column of deltaT with a constant indoor temp of 20C and multiply that by the 0.082 kWh/K. This results in a number that is pretty much the same as your usuagevfigure, which isn’t surprising as your average indoor temp is 19.9C, I.e. the same as the target temperature.

I think the reason that there is no real savings is that despite low insulation, your house has a high thermal mass, which means the indoor temperature doesn’t decrease enough to make a difference and while heating the house up it overshoots enough to give you and average temperature similar to your target temperature.

When we had a high temperature boilers we could heat the house just in the evening for a few hours, in which case the temperature would decrease enough to give real savings and maybe not heat enough to actually fully heat the fabric. Or we had single glazed leaky windows which meant the house cooled very fast.

Oh yes and we had mould on the walls…

@adrian — thanks. I'll see what I can come up with.

the principle is as probably described somewhere above, that the energy usage is directly proportional to the deltaT between outside and inside temperature.Posted by: @adrian

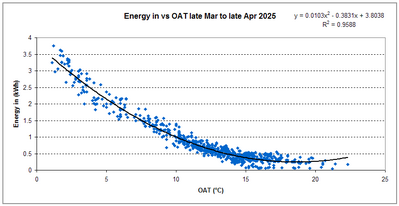

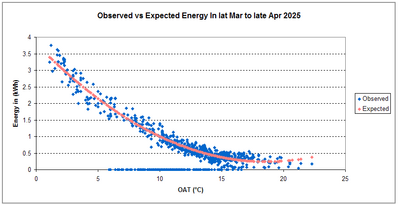

I don't think this is quite correct. The heat loss (and so, when the IAT is stable, the heat delivered to the building, ie the energy out) is directly proportional (ie linear) to the inside-outside delta t, but the energy usage ie energy in isn't linear, because COP declines at lower OATs (assuming a constant IAT). You need to put in more kWh per kWh out at lower OATs. This effect can be seen in this chart (reposted here for ease of reference):

Yes I know there is an anomaly at above around 18°C OAT, but strictly speaking that is outside the range we are interested in, and so an extrapolation, and thereby a warning against the dangers of extrapolation. For the range we are interested in, 0-16°C OAT, the line and so equation are a very good fit to the data.

Posted by: @adrianAs we don’t have the heat output numbers, I’m assuming a constant COP and calculate the kWh used per degree kelvin deltaT. This can be calculated as the sum of kWh used devided by the sum of deltaTs. This gives a number of 0.082kwh/K. Then I create a new column of deltaT with a constant indoor temp of 20C and multiply that by the 0.082 kWh/K. This results in a number that is pretty much the same as your usuagevfigure, which isn’t surprising as your average indoor temp is 19.9C, I.e. the same as the target temperature.

As noted and indirectly shown above, the COP isn't constant. In fact it can halve, as we can see here in the data plot for the relevant 24 hours (again a repost for ease of reference):

At 1800, the COP is around 5.5 with an OAT of around 14 and an in-out delta t of around 6°C. The following morning at 0700 it is around 2.5, with an OAT of around 2 and and in-out delta T of around 18°C. This alone means there isn't a constant kWh/in-out delta T of 0.082. Instead it varies: at 1800, with (numbers taken from the spreadsheet) an energy in of 0.33kWh and a in-out delta t of 6°C, it is 0.055, while at 0700, with an energy in of 3.30kWh, and an in-out delta t of 18°C, it is 0.183. As a result, using a constant value of 0.082kWh/in-out delta t to determine the expected values, you will over-estimate expected energy in at low in-out delta t values, and under-estimate expected energy in at high in-out delta t values. And this indeed what we see. Here are my expected values, with yours added alongside:

Up until 2100, when the setback starts, the differences aren't huge. But during the setback, and afterwards during the recovery period, when the OAT was lower and the in-out delta t greater, your and my expected values diverge considerably, with your expected values being less than mine. This happens because the constant kWh/in-out delta t value is too low at the lower OAT/in-out delta t values during this period.

Which expected figure is more likely to be closer to correct? We only need to look at the third column, which is the measured energy in, during the recovery period. Here we have a measured value against an expected (predicted) value. My expected values (column 4) are fairly close to and straddle the observed values in column 3, while your expected values in column 6 are considerably less than the observed values, sometimes to the extent of being half the observed values. It seems to me that any overall saving assessment based on those expected values cannot be relied upon.

I am also not sure about the general idea of using the in-out delta t as the determinant of the energy on, given the heat pump sets the LWT, and so indirectly the energy in, based on the OAT alone (which is in fact the air intake temperature on a Midea unit, but that is probably a red herring here). The in-out delta t may be proportional to the OAT when the IAT is constant, and so usable, but when the IAT varies, as it does, the in-out delta t will get out of step. It seems more sensible to me to use OAT values plotted against energy in values, and then use the regression equation from that plot, as I did.

Over to you!

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

PS by visually merging the two tables as above, I ended hiding your kWh/K column, which does show the values per hour:

If you multiply the hourly delta t by the hourly kWh/K value, rather than the 0.082 constant you do get the right expected values eg for 0400, 15 x 0.15786 = 2.3679 (which is the observed figure, given the maths). As I say, I think the problem is your use of a summary constant kWh/in-out delta t of 0.082, when in reality the value varies considerably, as can be seen in your table.

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Posted by: @cathoderayBut the odd things is, there is no obvious extra energy being put back in during the recovery period. Yet the recovery certainly happens, and in good time. There is no visible extra use during the recovery period to be offset against the undoubted savings during the setback, so in effect i get the full benefit of the setback.@jamespa — thoughts? Or anyone else?I'm not James but here's some thoughts...Have you tried to control for solar gain? And what about controlling for wind chill effects (speed and direction of the wind) and for humidity (greater probability and frequency of defrosts)? Any of these could account for your results. Also, you've assumed that once the IAT has recovered the house fabric has also returned to its pre-setback state, I'd suggest that this is not a safe assumption and the fabric will continue to re-absorb energy. As a result your calculated expected values include additional energy (thus inflated) as a result.On the flip side, during the recovery period the lower IAT will increase the radiator mean water temperature to IAT dT and so the output of your radiators will be slightly greater than at a higher IAT. And a lower IAT will require slightly less energy to maintain the lower IAT, so there will be a small excess of energy as your WC curve is set to maintain a greater IAT (and hence heat loss) which will raise the IAT slowly. But are those effects enough to explain a significant saving of energy? Probably not but could result in a small saving.

Good old physics tells us that it is impossible to not have to put extra energy in to get the temperature up without putting extra energy in. I havent seen anything in your numbers to indicate that the cop is significantly better during the recovery period, so I don’t see any gain there. Especially as the outside temperature from 22-4am is about the same as in the time period after that (and often lower).

As you say that your house is badly insulated, so it must be the thermal mass that leads to the slow loss of inside temperature and hence a low change in the inside outside delta.

if we knew your heat loss we can calculate what the one or two degree heat loss represents in terms of energy and calculate what that means. For example, assuming your heat loss is 7kw at deltat 22K:

7kW/22K=0.318 kW/K heat loss per degree.

so in the extreme case of iat dropping by 2 degrees over the six hours, so the average temperature will be 1 degree lower and have 1/22 less energy over that time that you would have if the heating had been on. But now you have to put that energy back in and by definition it’s the same amount of energy as you had lost. It looks like the time to recover varies somewhat, but even when the air temperature has recovered that building mass will still be recovering, so the iat does not represent the full picture of the recovery. Let’s say it takes 4 hours.

if oat was 5C during that time your heat loss is (19-5)/22*7=4.455 and would have been (20-5)/22*7=4.773 kw if the heating had been on. Your saving during that period has hence been (4.773-4.455)*6=1.908kwh. At cop 2 that is 1.908/3=0.636

so you didn’t heat the house for 6 hours to 1K below 20, so you didn’t put in 4.455kw*6=26.73 kW and will have to put that back in to heat the house up. if there was a difference of cop during these periods you could hence save additionally (let’s say cop 3 vs cop 4):

26.73kwh/3-26.73kwh/4=2.228 kWh

so your maximum electricity saving is less than 3kwh out of 24h*4.455kw/3.7=28.897 kWh.

the problem is that you could only get the improved cop if you switched it back on much later when the oat has improved, I..e. Middayish.

I suspect your curve fitting is to the data that includes the cutback and recovery and hence expects the usage during recovery.

Posted by: @cathoderayBut the odd things is, there is no obvious extra energy being put back in during the recovery period. Yet the recovery certainly happens, and in good time. There is no visible extra use during the recovery period to be offset against the undoubted savings during the setback, so in effect i get the full benefit of the setback.

@jamespa — thoughts? Or anyone else?

I apologise that I have been silent on this for a while, my mind has been elsewhere, not least fighting Vodafone (long story, in essence they are obstructing my desire (and right) for landline number portability and giving me the run around like there was no tomorrow).

I haven't yet caught up with all the above but from a quick read there seems to be some further progress. However my general feeling about this topic remains as it was and can be reasonably be summed up in:

- Unless the house cools significantly, the energy lost from the house cant reduce significantly during a setback relative to the no setback case. All energy lost from the house must be replaced to restore the house to its starting condition.

- If a house cools by only 2-3 degrees for a few hours, the percentage reduction in energy lost (and thus the reduction in energy we need to supply to the house) is very small. For example if it cools by a maximum of 3 degrees for 8 hours in 24, then the saving is very roughly 0.5*3/20*8/24, = 2.5%

Posted by: @adrian

- Good old physics tells us that it is impossible to not have to put extra energy in to get the temperature up without putting extra energy in.

- Until we can explain observations, however accurately recorded, or have sufficient robust statistical evidence, we cannot infer anything at all about how observations might apply to circumstances other than the specific ones in which they were made

I will try to get back to this once my telephone problems are solved (or when I have some time to spare where I am not in the place to solve them)!

4kW peak of solar PV since 2011; EV and a 1930s house which has been partially renovated to improve its efficiency. 7kW Vaillant heat pump.

There are some rather weird page layout things happening at the moment which I tried to fix by checking the underlying html (hence the notes saying I edited them attached to the above two comments, I didn't change any of the wording, just looked at the html). Putting that aside, here are my thoughts.

@robs — thanks for your thoughts. Solar gain (in daylight hours, not during the setback period and initial recovery) and wind chill may have had an effect on IAT, and defrosts certainly did (and on COP in the latter case), they can be seen in the chart (LWT below RWT) but what we are primarily looking at here is energy use, observed when it is known, and expected (predicted) when it is not known, eg what it would have been had I not had a setback. Observed is observed, and unless we are going to say my monitoring system is up the spout, which I don't think it is, then it is what it is. Yes. we should look very hard at whether the measurements are wrong, but I don't think they are, or if they are, they are only out by a small and not significant amount. The reason I think they are OK is that I have independent ways of checking the two key measurements, OAT and energy, a separate temperature data logger for the former, and an independent kWh meter for the latter. The OAT is very much a local OAT, because it is affected by the exhaust air coming from the heat pump, and so is more accurately the air intake temperature (AIT, the sensor is inside outdoor unit, on the air intake side), and it is typically a degree or two below the wider OAT, but we know that, and much more importantly the AIT is the primary, and primary by a long way, determinant of the set LWT temperature, and so ultimately the energy in. Never mind the R and R squared values, we can see that in this chart ( a repost added here for reference), there is a very tight correlation between the OAT/AIT and the energy in:

The scatter about the line is random variation which is to be expected, indeed I would be rather worried if it wasn't there. @adrian "I suspect your curve fitting is to the data that includes the cutback and recovery and hence expects the usage during recovery." No, this plot is only for data points when the heat pump was running, it includes recovery periods but not the setbacks. It is also space heating only, no DHW heating.

What that chart tells me is that I can make valid predictions about the energy in, ie expected values, once I know the OAT/AIT. Indeed, when I do that (make predictions), the predicted (expected values) fall where they should. There is of course an air of self fulfilling prophesy about this, since I am in effect just reversing the mathematics, but that just underlines how robust this method is. It just works (the observed values on the X axis are setback hour values, zero energy in):

The predicted (expected) values are exactly where they should be. This model (because that is what it is, even if I don't use that term) works. Given an OAT/AIT, we can very accurately predict the energy in. Yes in the real world there will be some random variation, but when we come to sum the hourly values over a longer period (24 hours), the randomness means the variations will cancel themselves out.

The essential point here is that the equation (shown in the upper chart above) is the best predictor we have of expected energy in values, given a known OAT/AIT. Behind the scenes, it takes into account all of the physics, both that which we know about, and that which we don't know about, and gives us a summary in that equation.

"Also, you've assumed that once the IAT has recovered the house fabric has also returned to its pre-setback state, I'd suggest that this is not a safe assumption and the fabric will continue to re-absorb energy. As a result your calculated expected values include additional energy (thus inflated) as a result."

I am not sure about this. The IAT is what matters to the inhabitants. If the fabric is still re-absorbing energy despite a recovered IAT, and I agree it may be, the heat pump and it's control logic doesn't know this (it doesn't know what the IAT is, let alone the energy flux in the fabric), it only knows and only uses the OAT/AIT to set the set LWT and so in due course the energy in. Yes, it does also know the RWT, but, subject to being corrected, because this is a grey area that may be relevant, I don't think that is used in any way to set the LWT, which is merely derived from the WCC.

Furthermore, I think your logic may be the wrong way round. If the house is in reality somehow sucking in more energy during the recovery period, then my predicted/expected should be too low (ie deflated, rather than inflated) as a result. But in fact they are neither: the predictions match the observations.

@adrian — "Good old physics" - next you will be invoking "old Father time"! My contentions is that empirical results, once you have ruled out measurement error, always trump theoretical results. I don't doubt the laws of physics for one second, but I can and sometimes do doubt their application. If a theory (model) comes up with a different answer to the observed data, then there is something wrong with the model, and it need to be revised. That is the scientific method. Hypotheses, test, modify. My very simple model works, the predicted (expected) values are very close to the observed values when we have both. If we have another hypothetical model that incorporates other factors and somehow produces a different answer that doesn't fit the facts (observed values), then we need to look again at that hypothesis.

"I havent seen anything in your numbers to indicate that the cop is significantly better during the recovery period, so I don’t see any gain there." It is visibly worse, unsurprisingly as the OAT is lower, and there are defrost cycles.

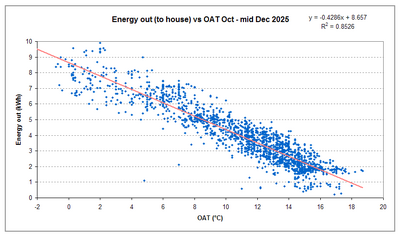

"if we knew your heat loss we can calculate what the one or two degree heat loss represents in terms of energy and calculate what that means." We do know what my heat loss is, a monitored heat pump makes this easy to measure. Given a steady IAT, the heat loss = the energy delivered to the building, ie energy out from the heat pump. So far this season, I have been running without a setback, and the IAT has been pretty steady for most of the time, with some milder weather followed by some colder nights:

I can plot hourly mean OAT against hourly energy out ie delivered to the house:

which suggests a heat loss of 9.5kWh per hour (9.5kW). The outliers? Not enough of them to matter.

"At cop 2 that is 1.908/3=0.636" — no doubt an innocent typo, but that should be "At cop 2 that is 1.908/2=0.954". But the real problem I see with your method is that it relies on energy out, and then assumptions about COP to derive energy in. That is two places where error can creep in, the assumptions about energy out, and the assumptions (let's face it they are guesstimates) about COP. My method on the other hand (a) relies on energy in which is more robust and is directly the number we are interested in and (b) makes no assumptions about COP, because it doesn't need to. Put prosaically, my method points a finger at the face of the moon, whereas your points at the dark side of the moon, and then comes to some conclusions about the light side of the moon.

That said, I think it might be possible to do a more robust calculation using your method. We do have all the data we need, IAT, OAT, the heat loss equation (above, which could be redone with inside/outside delta T on the X axis), to determine the heat loss, and we could estimate the COP at various OATs. We could then do an hour by hour calculation, and finally sum them over 24 hours. But do we need to do that? I'm not sure we do, but then again it might be interesting to do it.

I also have some concern about an excessive focus on the energy balance in the fabric. What matters to the inhabitants is not that energy balance, but the IAT. Is it possible that while the IAT is OK, the house is still out of balance, and so in fact the conservation of energy (which I don't dispute) doesn't apply in the short term, but only in the (much) longer term? Yes, the house loses X amount of energy during the setback, and X ultimately needs to be put back in, but what about the short term. Maybe the fabric is forever playing catch up, while the IAT is OK for the inhabitants? My earlier question about the duration of setback is relevant here: longer setbacks (days or weeks) do mean real savings. At what point, and why, do the savings start to become more questionable?

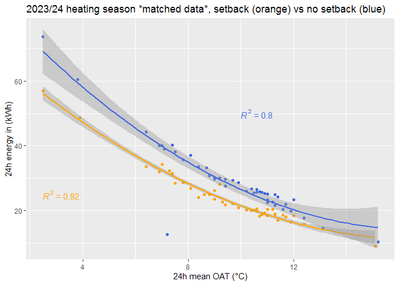

Finally at the end of a rather long post, there is this chart:

from this post, which gives more detail and a statistical analysis, but in brief this uses a quasi-epidemiological method to attempt to answer the question: are setback and non-setback days both part of the same general population (ie no difference between them) or are they each part of their own independent population (ie they are fundamentally different). This plot (done in R) includes the 95% confidence intervals (grey shaded areas), and visually it strongly suggests two different populations ie they are fundamentally different. The statistical analysis (which may be open to challenge) concluded "The setback running as recorded in this data set appears to use about 20-23% less energy compared to no setback running."

I must repeat again a truth universally acknowledged, that this is a single analysis in want of a singular answer. It only applies to my house in the conditions that applied during the time period under analysis.

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Posted by: @jamespanot least fighting Vodafone (long story, in essence they are obstructing my desire (and right) for landline number portability and giving me the run around like there was no tomorrow).

If it's any comfort (of the you are not alone variety) I have a very similar long running problem with Plusnet. It's like arguing with a brick wall.

BTB the page layout problem with this forum page persists at least for me, but I can now at least select text and have it placed in a quote in the comment I am writing. For my last post that didn't happen, so I had to manually "put quotes in quotes".

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

- 27 Forums

- 2,520 Topics

- 58.6 K Posts

- 741 Online

- 6,800 Members

Join Us!

Worth Watching

Latest Posts

-

RE: Daikin Altherma 3 LT compressor longevity question

This mess is intriguing: I wonder if this represent...

By bobflux , 12 minutes ago

-

RE: Say hello and introduce yourself

Hi. I'm Mike. Thank you for letting me join. My partn...

By Fretless6 , 2 hours ago

-

RE: Connecting Growatt SPH5000 over wired ethernet rather than wireless

The simplest wired option is usually the Growatt Ethern...

By Jonatan , 4 hours ago

-

RE: Peak Energy Products V therm 16kW unit heat pump not reaching flow temperature

ASHPs do have a minimum compressor speed. The minimum h...

By bobflux , 11 hours ago

-

RE: Electricity price predictions

@jamespa And it seems some of the nasty public cloud...

By Batpred , 11 hours ago

-

RE: Tell us about your Solar (PV) setup

Location: near Lyon, France 12kWp on the roof, 2x Sol...

By bobflux , 12 hours ago

-

RE: Jokes and fun posts about heat pumps and renewables

Technology is rapidly advancing. BBC News reported th...

By Transparent , 15 hours ago

-

What matters for flow and pressure drop is internal dia...

By bobflux , 15 hours ago

-

RE: Do Fridges and Freezers have COP ratings?

@editor Thank you all for your replies and submitted in...

By Toodles , 18 hours ago

-

I know and yes. The secondary deltaT wont necessaril...

By JamesPa , 22 hours ago

-

RE: Designing heating system with air to water heat pump in France, near Lyon

Just love the way you put it! 🤣

By Batpred , 2 days ago

-

RE: Safety update; RCBOs supplying inverters or storage batteries

Thank you for sharing. So it seems that your Schneid...

By Batpred , 2 days ago

-

RE: Forum updates, announcements & issues

@upnorthandpersonal thanks for the thoughtful, consider...

By Mars , 2 days ago

-

RE: Solar Power Output – Let’s Compare Generation Figures

@mk4 All 21 panels have their own Enphase IQ7a microinv...

By Toodles , 2 days ago

-

RE: Setback savings - fact or fiction?

Great, so you have proven that MELCloud is consistently...

By RobS , 3 days ago

-

RE: Mitsu PUHZ120Y 'Outdoor Temp 'error?

Thanks David & James It almos...

By DavidAlgarve , 3 days ago

-

RE: Surge protection devices SPDs

@trebor12345 - your original Topic about the right type...

By Transparent , 3 days ago

-

RE: Help needed with Samsung AE120RXYDEG

@tomf I’ve been sent this from a service engineer at Sa...

By Mars , 3 days ago

-

RE: Buying large amp bidirectional RCD and RCBO

Yes... I went through this particular headache and ende...

By bobflux , 4 days ago

-

O-oh! Let's take this as an opportunity to 'pass the ...

By Transparent , 4 days ago

-

RE: Homely setup on daikin heat pump

@craigh I refer to our somewhat elevated temperature of...

By Toodles , 4 days ago

-

RE: Air source heat pump roll call – what heat pump brand and model do you have?

My turn, this describes the future installation, only t...

By bobflux , 4 days ago