Posted by: @sunandairJames, can you remind me what is your definition of setback, in terms of temperature? What are you defining as target daytime room temperature and what is the number of degrees below this temperature is your setback? Or are you not targeting room temperature at all?

if you are using weather compensation how are you operating a setback at night? I don’t control Weather compensation since I am using Auto Adaptation which reacts to set room temperature.

@jamespa is using my data, meaning I can explain how the setbacks are done, and the other factors involved:

(1) my system is always on weather compensation (but see (3) below, because this can vary) and most of the time during continuous running the IAT is around 18-19 degrees (desired IAT is 19 degrees; at this moment in time 10:03, it is exactly 19.0 degrees)

(2) a setback is achieved by using a timer to set the room stat from 26 degrees (normal running, ie always on because IAT never gets to 26 except rarely in summer) to 12 degrees (effectively, always off, because during the setback the IAT doesn't fall that much - typically it drops between one and three degrees). The duration of the setback is 2100 - 0300, 6 hours or 25% of a 24 hour period

(3) in addition to running weather compensation all the time, I also have an auto-adaption python script that compared the actual IAT to the desired OAT, and if there is a discrepancy, it adjust the weather compensation curve by moving the left and right hand end points. At the moment, for each degree the actual IAT is below the desired IAT, it moves the WCC endpoint up by one degree, up to a maximum of a three degree increase; and vice versa for when the actual IAT is above the desired IAT (not that that happens very often). I think this is similar to, but not the same as, the Ecodan Auto-Adaption, the idea being in both cases to deal with the fact that heat pumps running in WCC mode are sluggish beasts, and they need a kick up the backside to get then going if there is harder work to do, eg recovery from a set back

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Posted by: @jamespaThere is no mention of savings due to not running circulating pumps because

a) their energy consumption doesn't feature in any of the experimental data or the model which are being discussed and

b) in almost, if not all, all situations of interest, the energy consumed/power needed by a circulating pump is negligible in comparison with the energy required to heat the house.

(a) this is in fact something of an unknown. The external kWh meter reads all energy going in to the heat pump, and as both circulating pumps are supplied from the heat pump, that external meter value does include whatever the pumps use. The calculated kWh in (amps x volts as reported by Midea) is almost always less than the external meter value, and I have speculated (that's as good as it gets, because I don't know how or where Midea measure the volts and amps) that the discrepancy may be due to the circulating pump (and possibly some other) use being excluded from and amps/volts values. The discrepancy is of the order of 18%, and has bee factored into the calculations in the spreadsheet.

(b) I am not sure we can say this, unless we know what the combined pump use is. It is clearly not going to be huge, but it may nonetheless be visible.

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Posted by: @cathoderayPosted by: @sunandairJames, can you remind me what is your definition of setback, in terms of temperature? What are you defining as target daytime room temperature and what is the number of degrees below this temperature is your setback? Or are you not targeting room temperature at all?

if you are using weather compensation how are you operating a setback at night? I don’t control Weather compensation since I am using Auto Adaptation which reacts to set room temperature.

@jamespa is using my data, meaning I can explain how the setbacks are done, and the other factors involved:

(1) my system is always on weather compensation (but see (3) below, because this can vary) and most of the time during continuous running the IAT is around 18-19 degrees (desired IAT is 19 degrees; at this moment in time 10:03, it is exactly 19.0 degrees)

(2) a setback is achieved by using a timer to set the room stat from 26 degrees (normal running, ie always on because IAT never gets to 26 except rarely in summer) to 12 degrees (effectively, always off, because during the setback the IAT doesn't fall that much - typically it drops between one and three degrees). The duration of the setback is 2100 - 0300, 6 hours or 25% of a 24 hour period

(3) in addition to running weather compensation all the time, I also have an auto-adaption python script that compared the actual IAT to the desired OAT, and if there is a discrepancy, it adjust the weather compensation curve by moving the left and right hand end points. At the moment, for each degree the actual IAT is below the desired IAT, it moves the WCC endpoint up by one degree, up to a maximum of a three degree increase; and vice versa for when the actual IAT is above the desired IAT (not that that happens very often). I think this is similar to, but not the same as, the Ecodan Auto-Adaption, the idea being in both cases to deal with the fact that heat pumps running in WCC mode are sluggish beasts, and they need a kick up the backside to get then going if there is harder work to do, eg recovery from a set back

I have nothing to add to this in answer to the question posed.

More generally I would suggest that 'setback' is any deliberate act to switch off or turn down the heating temporarily for the purpose of saving money or increasing comfort during the set back period (generally night time), where the heating is controlled in a way which restores the indoor temperature to its design value at some reasonable point after the heating has been switched back on again.

The question posed in this thread is 'does set back save energy without compromising comfort?' and we are concentrating on setbacks where setback and recovery both take place within 24hrs (and most likely are repeated on a daily cycle). For longer setbacks, eg a fortnight's vacation, the answer to the question is definitely 'yes'. ToU tariffs are not considered at the current time, the focus is purely on energy.

Its become clear from experiment, modelling and theory, that this question is much more difficult to answer than it might first appear. I think its also become clear that its all too easy to misinterpret results, whether experimental or from modelling, in a way which materially exaggerates any possible energy saving, because they are not comparing like for like (and in particular not accounting for changes in energy stored in the fabric, which eventually must be replaced).

I would say that the current state of analysis (experimental, theoretical, and modelled), suggests, but only suggests, that a 6-12hr setback may save up to ~5% of the total daily energy consumption in some circumstances, but in other circumstances may result in the consumption of more energy. So at best its marginally worth doing and at worst may actually be counterproductive. However (following fairly robust peer review!) none of the methods are yet sufficiently refined for this to be a certain conclusion.

I think the bigger message is probably 'relax', it isn't likely to be a disaster or make a huge difference if you don't apply setback, but equally it isn't likely to be a disaster or make a huge difference if you do, a message rather neatly summed up by @scrchngwsl in this post

What I would personally avoid, based on the limited results so far, is applying setback and as a result feeling cold when you are supposed to feel warm, and reacting by turning up the heating temperature! The result of this is highly likely to more than counteract any possible savings through setback.

4kW peak of solar PV since 2011; EV and a 1930s house which has been partially renovated to improve its efficiency. 7kW Vaillant heat pump.

Posted by: @cathoderayPosted by: @jamespaThere is no mention of savings due to not running circulating pumps because

a) their energy consumption doesn't feature in any of the experimental data or the model which are being discussed and

b) in almost, if not all, all situations of interest, the energy consumed/power needed by a circulating pump is negligible in comparison with the energy required to heat the house.

(a) this is in fact something of an unknown. The external kWh meter reads all energy going in to the heat pump, and as both circulating pumps are supplied from the heat pump, that external meter value does include whatever the pumps use. The calculated kWh in (amps x volts as reported by Midea) is almost always less than the external meter value, and I have speculated (that's as good as it gets, because I don't know how or where Midea measure the volts and amps) that the discrepancy may be due to the circulating pump (and possibly some other) use being excluded from and amps/volts values. The discrepancy is of the order of 18%, and has bee factored into the calculations in the spreadsheet.

(b) I am not sure we can say this, unless we know what the combined pump use is. It is clearly not going to be huge, but it may nonetheless be visible.

We can look at the specifications of typical circulating pumps. Here is a common one, 60W = 1.4kWh/day assuming its operating at max (which most circulating pumps don't). The average daily consumption in your data is 29kWh. So I think we can say that the energy consumed by the pump is negligible in comparison with the energy required to heat the house.

Turning it off for 12hrs each the day would however save (a maximum of) 2.4%. That of the same order as the likely savings through setback, but a 12 hr setback with the pump operating at maximum is a fairly extreme case. I don't know if your reported energy consumption includes the pump or not. Either way I concede it does make a small difference, but one that is currently well within the margin of error on the calculations.

4kW peak of solar PV since 2011; EV and a 1930s house which has been partially renovated to improve its efficiency. 7kW Vaillant heat pump.

@jamespa - perhaps more importantly, recall that we are using a corrected energy in, the 1.18 correction factor that (on average) brings the calculated energy in value up to (mostly) match the external kWh meter value, which definitely does include the circulating pumps, and indeed any other unknowns, that are supplied from within the heat pump. The circulating pump use is therefore already in the calculations, we just don't know exactly what it is (and in fact don't need to know, if all we are interested in is total energy use).

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Posted by: @cathoderay@jamespa - perhaps more importantly, recall that we are using a corrected energy in, the 1.18 correction factor that (on average) brings the calculated energy in value up to (mostly) match the external kWh meter value, which definitely does include the circulating pumps, and indeed any other unknowns, that are supplied from within the heat pump. The circulating pump use is therefore already in the calculations, we just don't know exactly what it is (and in fact don't need to know, if all we are interested in is total energy use).

That's most helpful thanks, and as you say we don't really need to know exactly the energy consumption of the pump if its already included.

4kW peak of solar PV since 2011; EV and a 1930s house which has been partially renovated to improve its efficiency. 7kW Vaillant heat pump.

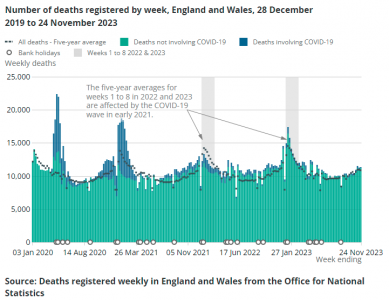

I haven't forgotten there is at least one other way to approach this problem: compare the observed energy use during a setback with the expected energy use without a setback. The idea of comparing observed values with expected values is widely used in epidemiology - for example, it is used by ONS (Office for National Statistics) to calculate excess mortality (source: ONS):

While the basic principle of the method could not be simpler, there are two problems with execution. The first is how do you estimate the expected number, and the second is how do you account for other factors (changes for example in population size, or age distribution, over time) that could explain any excess. For example, if a population grows in size by 10%, then there will be 10% more deaths, even when the mortality rate remains constant. Accounting for changes in other factors is commonly dealt with by standardisation, that is, by adjusting, or standardising, the rates to another known or arbitrary population. Determining the basis for the expected number is more problematic, and at the end of the day is a judgement call. ONS for example use an ad hoc preceding five year average for the above chart which includes some covid time, which has the effect of increasing the expected number, and thereby decreases the excess number, of deaths. I personally prefer to use 2015 - 2019: that way we compare pre-covid arrival with post-covid arrival. It is worth noting that this is all cause mortality, undoubtedly and by far away the most reliable number in all epidemiology. ONS's habit of getting the crayons out to colour covid deaths is a red, or in this case, blue herring, largely because their definition of a covid death is profoundly greedy. What we are really interested in is all cause mortality, whether from covid, or from other pernicious effects related not to covid per se, but our responses to covid.

I mention excess deaths to show that the principle of comparing observed and expected values is an established method. Coming back to heat pumps: I have minute by minute (and so also hourly, daily, weekly, whatever) data on energy use by my heat pump, both for energy in (consumed) and out (produced). That means I know, within the limits of measurement accuracy, which is not too bad, based on validation against an external kWh meter, what, for any one hour (a convenient interval in the circumstances), what the energy in (consumed) was for that hour. Note that all that follows uses corrected calculated heating (not DHW) energy in data, ie the calculated (volts x amps) heating energy in has been multiplied by the 1.18 correction factor to bring it into line with the external meter reading values.

There have been periods when I have run my heat pump continuously, and periods when I have had an overnight setback. What I need is an estimate of the 24 hour expected energy in would have been, had I not had a setback. I can then compare this to the actual known observed 24 hour energy in during a setback period. Any difference will represent an estimate of the energy saved (or extra energy used, if the observed is greater than the expected).

Now, I don't think that it is too difficult to devise a way to do this. In normal (continuous) weather compensation curve (WCC) running, my indoor air temperature, IAT, stays fairly constant (the exception is cold snaps). This means that the main (only?) determinant of energy consumption is the outside air temperature, OAT, since it, via the WCC, controls the Set LWT, and so ultimately the energy consumption. I can therefore plot the hourly mean OAT against the energy in for that hour, and determine the relationship between the two. Once I have that relationship, expressed as an equation, I can then calculate the expected energy in for any given hour, based on the OAT for that hour.

Bingo! I now have both observed and expected energy in by hour, meaning I can sum each over a 24 hour period, and determine how much less (or more) energy I have used during a setback, compared to what I would be expected to have used, without a setback.

Note that in contrast to methods that rely of models of varying complexity, the approach described here relies almost exclusively on observed data, with only minor inferences, well within the bounds of reason. In other words, there is no black box, everything is out in the open, and based on observed data. Also note that I do make some assumptions (MOAFUs), but I shall attempt to show they are reasonable, if not perfect.

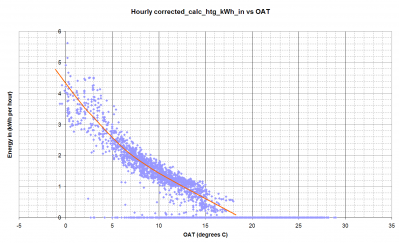

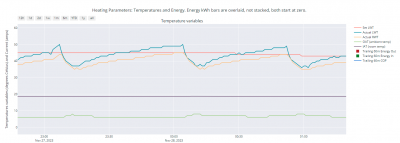

I start with the entire hourly data set, which covers a period from late March 2023 to date. This data set has over 6000 rows, more than enough data points to be getting along with. Step 1 is to plot corrected (1.18 factor, see above) calculated heating energy in against OAT, and this is what I get:

There is of course a lot of noise (this is real world data) but a clear relationship appears to be present, represented by the sketched orange line I have added to the chart. It is not linear, but that is to be expected, because efficiency (COP) falls as OAT falls, meaning a heat pump uses relatively more energy at lower OATS compared to higher OATs.

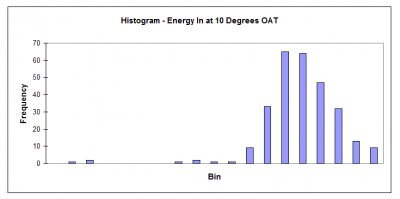

Now, the next step assumes the values for each OAT are normally distributed, ie they have a symmetrical distribution (as many above as below) about a mean, or average. If that is the case then the mean has meaning, it is a representation of the average at that OAT, and can be used to estimate the expected energy use on average for a given OAT. In other words, it accommodates, and in effect deals with the variation, or noise. There are various fancy statistical tests for normality in a distribution, but I find the Mk 1 Eyeball can do the job just as well, and more convincingly. From the above scatter plot, I already get a sense of normality, but what happens if I look at the spread for a particular OAT, say 10 degrees? Here's the histogram:

There are definitely some outliers, which I can ignore, as they are very few. The question is does the main bulk of the distribution have a bell shaped curve, ie as many values above the mean as below, and I think the answer is yes, it is a good enough bell shaped curve. There is a bit of left skew, but not enough to have me wetting my pants.

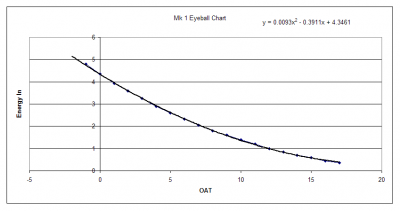

With this test done, I then made a custom chart of energy in vs OAT by reading off the values at each OAT from the earlier chart. This is just a shorthand way of getting the equation that describes the relationship: by fitting a trend line, I can also get the equation:

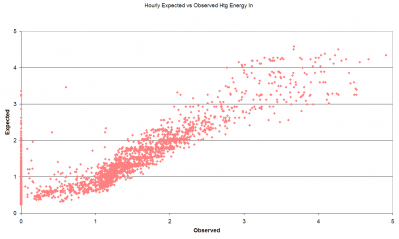

That equation in the top right hand corner is the equation that describes the relationship between OAT and energy in. I decided to check its capabilities by plotting the expected energy in against the observed energy in for all the data I have (including when the heating was off, which accounts for the zero observed values). This is the result:

There is quite some spread, especially at higher values, but I am reasonably confident that on average (meaning errors either side will cancel out) for most of the time the equation can predict an expected energy in that is indeed not that far from the observed OAT for any given hour. Of course, at the individual hour level there will be errors, but they will, on average cancel themselves out. This means I can now use this equation to calculate what the energy in would have been (because the OAT sets the energy in) during and after a setback, had I not had the setback. The fact that the IAT when not in setback mode remains constant helps here, as again it means the main (only?) determinant of energy use is the OAT.

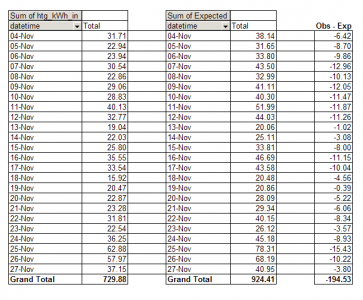

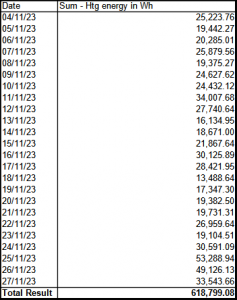

I have a just over three week period in November when I had a six hour overnight setback from 2100 to 0300. In addition to the setback, I also had my auto-adapt python script running. This adds a recovery boost whenever the actual OAT falls one or more degrees below the desired OAT, so as to put back the heat lost during the setback in a reasonable period of time. Using a pivot table, I pulled out the daily total observed and expected energy in values for this three week period, and then subtracted the expected from the observed. This is what I got:

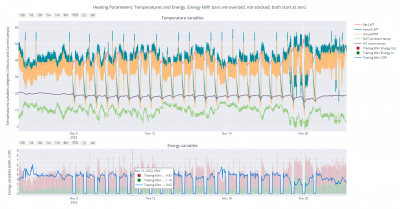

Now, I am not for a moment suggesting that this is a perfect analysis that gives a definitive answer. I do nonetheless think that it suggests energy savings are possible. Furthermore, it satisfies the 24 full energy accounting requirements (ultimately tested by whether the average IAT stays constant over longer periods of time, which it does, see below), and while there was some minor loss of comfort, caused by a lower than ideal OAT on some mornings, it was not dire. Here is my routine monitoring data for the period setbacks were in use, and a few days either side:

I think what has happened is I have traded a few hours of overnight chilling, when it doesn't matter, because I am tucked up in bed, for a few, but not unsubstantial, number of kWhs of energy saved. On the basis of what I have presented in this post, I suggest the answer to the original question, do setbacks save energy without compromising quality, is a qualified yes, the qualification being there is a minor impairment to quality. That minor impairment might well be amenable to correction by a more aggressive auto-adapt regime, but at a cost of a bit more energy used.

Of course, I may have made some awful blunder. Any and all comments very welcome.

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

The technique is certainly valid and should give a very similar answer to the technique of comparing the two distributions, provided the necessary corrections are taken into account in both cases.

From your text I presume that these are midnight to midnight values. According to your data the IAT at 2023-11-04T00:00:37 was 19.9C, and at 2023-11-27T23:59:05 was 18.6C, a difference of 1.3C. The OAT was actually the same at both times, namely 6C, however it went down to 5C one minute after the start of the period and up to 7C 7 minutes after the end, so I think we can infer that there was an OAT difference of nearly 2C.

From the correlation exercise we know that this means approximately 1.3*17kWh less - 2*2kWh was stored in the fabric at the end of the period than was the case at the beginning of the period, a correction of 18kWh to the house, that/cop in terms of energy in. This is small compared to the difference you are observing. My concern is that I think that the saving you are apparently seeing is more than can be accounted for by the saving in loss from the house, and if this is the case then where is the saving coming from? Can you share your analysis so I can have a look please?

4kW peak of solar PV since 2011; EV and a 1930s house which has been partially renovated to improve its efficiency. 7kW Vaillant heat pump.

Wow, a 30.71% reduction in energy consumption on 8th November, with an overall reduction of 21.04% for the whole period. Truly unbelievable.

Posted by: @jamespaThe technique is certainly valid and should give a very similar answer to the technique of comparing the two distributions, provided the necessary corrections are taken into account in both cases.

I agree, but at the moment the results are quite far apart. That is what we have to reconcile. One method is over-correcting, or the other is under-correcting, or perhaps both are partly out of whack.

Posted by: @jamespaFrom your text I presume that these are midnight to midnight values. According to your data the IAT at 2023-11-04T00:00:37 was 19.9C, and at 2023-11-27T23:59:05 was 18.6C, a difference of 1.3C. The OAT was actually the same at both times, namely 6C, however it went down to 5C one minute after the start of the period and up to 7C 7 minutes after the end, so I think we can infer that there was an OAT difference of nearly 2C.

Yes, they are midnight to midnight values, as that is the way the data naturally organises itself, and is the way the pivot tables natively group, by day is midnight to midnight. I am also naturally lazy, and won't complicate an analysis when it doesn't need to be complicated (and in fact there is a virtue in that, less steps means less opportunities for errors)! I took the view that in fact any 24 hour period was valid (so the decision on what to use is in fact arbitrary), as long as 'full accounting' is done within each 24 hour period. I further took the view, as mentioned briefly in the post, that if the average IAT stayed stable over longer periods, then there was no net loss (or gain). I was trying to bypass all the other calculations, and their moment by moment wobbles (noise), by looking at the net result. Don't forget that I coincidentally (and unfortunately perhaps, as it complicates things a bit) lowered the WCC a bit either just before or at the start of the setback period, as the house had been running a bit hot (see left hand end of the long timeline plot).

The OAT variations you mention are cycling artefacts (OAT rises when compressor stops, falls when it starts again):

Also bear in mind the method presented here uses hour, not minute data, and the hourly averages smooth out out the noise. For example the hourly average OAT at the start of the period, recorded at 2023-11-04T01:01:01 (for the previous hour) is 5.3, and at the end of the period, recorded at 2023-11-28T00:01:00m is 6.2, both of which seem fair enough given the above charts.

Equally, I don't even use the IATs in the calculations at all: all I did was look at the net energy balance, and it was stable (avg IAT stays the same over longer time frames), as it did (see earlier time line chart, there is no net loss until right at the end, when a marked drop in OAT put my heat pump into can't quite cope defrost cycle territory).

I suppose you could say the method used here is akin to just looking at the bank balance of a company from time to time: it it remains healthy on a day to day basis then all is well, and you don't have to do all the minutiae of the calculations, because they have been done for you by the ghost in the machine, as it were. Or to use the lake analogy, as long as the average level remains constant over time, then there has been no net loss of gain of water (energy), and you know that, without having to do minute by minute calculations. The steady balance (average level) gives you the answer.

A couple of other comments:

(a) because I used midnight to midnight periods, the first and last two periods are not typical, as they only have 3 rather than six hours of setback. I should perhaps have excluded them from the analysis

(b) a reminder that the overall drop from before to after the set back period is a net loss, but it is a deliberate one, caused by lowering the WCC a bit. It is not a result of running setbacks. In keeping with (a) really the period to be looking at is from say 6th of November, when the IAT has settled at the lower temp, and the 24th November, the last day before heat pump goes into CQC (can't quite cope) mode.

Here's the spreadsheet, bear in mind it is hour data so it won't exactly match the minute data as the hours use averages and and sums etc. Also note that I baked in the 1.18 correction (did an in-situ multiply by, so you can't see it, only the result) right at the beginning (that's what the htg_in_corrected in the file name means, so I know this file has corrected heating energy in (which is what I used, but not the other energy in values) data in it ). The Copy (3) is because I always work on copies of the original data file so the original doesn't get messed up.

It's a bit messy but I am sure you will work out what is going on:

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Thanks

I agree that the less processing the better. I used noon to noon data only because that's what you had previously quoted in your posts. Its much easier to use midnight to midnight. Ideally we would do this from the raw data that comes out of the midea so as further to reduce the data processing.

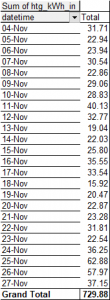

As a first observation, if I take your minute data and run a pivot to get total heating energy (volts*amps*1.18) in I get these results

Whereas your spreadsheet (final page) says this

The ratio between the two is 1.18, which is obviously more than a little suspicious

That potentially makes the difference between expected and actual even bigger (depending on how expected was calculated), but I until we have reconciled the minute data with the hourly data I don't think we cant be certain of anything. Also it might not make much difference to the comparison as the 'expected' is likely based on the same data which also differs, but in the same way, from the minute by minute data.

In your pivot table how did you get the data to display by date rather than by date and hour. I cant seem to reproduce that.

Also can you explain how you got the trendline. The Mk1 eyeball method almost certainly ignores overlapping points, particularly those on the axis (heating energy = zero). But at least some of these these matter because there are quite a few hours when the heating energy is zero (or reduced) because there is DHW heating going on or for other reasons, and these need to be counted otherwise the expected energy might be overestimated. If I get excel to put an order 2 trendline on the data, it falls a long way below the 'eyeball' trendline, but I grant that this may include zero values that should be excluded.

Also, using the Mk1 eyeball average, your IAT during the setback period was typically about 19.5C whereas during October it was more like 20-20.5 for quite a lot of the time. That is not insignificant and is, for laudable simplicity, ignored in your calculation. We don't know what the IAT was in March/April but the data is included in the trendline.

As I say above the difference you appear to show is, I think, too great to be explained only by savings in losses from the house during setback. That being the case I also believe that we need to look for other explanations to get a fuller picture of whats going on.

4kW peak of solar PV since 2011; EV and a 1930s house which has been partially renovated to improve its efficiency. 7kW Vaillant heat pump.

- 27 Forums

- 2,495 Topics

- 57.8 K Posts

- 541 Online

- 6,220 Members

Join Us!

Worth Watching

Latest Posts

-

RE: Humidity, or lack thereof... is my heat pump making rooms drier?

That’s my pleasure, @andrewj. The only challenge now is...

By Majordennisbloodnok , 8 minutes ago

-

RE: Electricity price predictions

@toodles @skd Then there is not going to be much from t...

By ChandyKris , 53 minutes ago

-

RE: Solis inverters S6-EH1P: pros and cons and battery options

@batpred I reckon Andy might know a thing or 2 about...

By Bash , 1 hour ago

-

RE: What determines the SOC of a battery?

@batpred Ironically you didn't have anything good to...

By Bash , 2 hours ago

-

RE: Testing new controls/monitoring for Midea Clone ASHP

Here’s a current graph showing a bit more info. The set...

By benson , 3 hours ago

-

RE: Setback savings - fact or fiction?

True there is a variation but importantly it's understa...

By RobS , 3 hours ago

-

Below is a better quality image. Does that contain all ...

By trebor12345 , 3 hours ago

-

Sorry to bounce your thread. To put to bed some concern...

By L8Again , 3 hours ago

-

@painter26 — they (the analogue gauges) are subtly diff...

By cathodeRay , 4 hours ago

-

Our Experience installing a heat pump into a Grade 2 Listed stone house

First want to thank everybody who has contributed to th...

By Travellingwave , 7 hours ago

-

RE: Struggling to get CoP above 3 with 6 kw Ecodan ASHP

Welcome to the forums.I assume that you're getting the ...

By Sheriff Fatman , 10 hours ago

-

RE: Say hello and introduce yourself

@editor @kev1964-irl This discussion might be best had ...

By GC61 , 12 hours ago

-

RE: Oversized 10.5kW Grant Aerona Heat Pump on Microbore Pipes and Undersized Rads

@uknick TBH if I were taking the floor up ...

By JamesPa , 1 day ago

-

RE: Getting ready for export with a BESS

I would have not got it if it was that tight

By Batpred , 1 day ago

-

RE: Need help maximising COP of 3.5kW Valiant Aerotherm heat pump

@judith thanks Judith. Confirmation appreciated. The ...

By DavidB , 1 day ago

-

RE: Recommended home battery inverters + regulatory matters - help requested

That makes sense. I thought better to comment in this t...

By Batpred , 1 day ago

-

Bosch CS5800i 7kW replacing Greenstar Junior 28i

My heat pump journey began a couple of years ago when I...

By Slartibartfast , 1 day ago

-

RE: How to control DHW with Honeywell EvoHome on Trianco ActiveAir 5 kW ASHP

The last photo is defrost for sure (or cooling, but pre...

By JamesPa , 1 day ago

-

RE: Plug and play solar. Thoughts?

Essentially, this just needed legislation. In Germany t...

By Batpred , 1 day ago

-

RE: A Smarter Smart Controller from Homely?

@toodles Intentional opening of any warranty “can of wo...

By Papahuhu , 1 day ago

-

RE: Safety update; RCBOs supplying inverters or storage batteries

Thanks @transparent Thankyou for your advic...

By Bash , 2 days ago

-

RE: Air source heat pump roll call – what heat pump brand and model do you have?

Forum Handle: Odd_LionManufacturer: SamsungModel: Samsu...

By Odd_Lion , 2 days ago

-

RE: Configuring third party dongle for Ecodan local control

Well, it was mentioned before in the early pos...

By F1p , 2 days ago