Posted by: @transparentAnd what perceived benefit does one get from spending £550-ish on such a pump?!

I only checked the price today. Hitherto I thought the installer’s costs were quite low. I paid £18k (less BUS grant) for 22 rads to match heat losses calculated at 12kW, 12kW Midea, 210l Tempest DHW cylinder and 16kW plate heat exchanger. No new pipework to rads.

Yes, the Wilo is inside.

Phil

@filipe - it does sound like an odd design/system. 12kW heat loss, 22 rads, that's give or take 500W on average output for each rad which even at ASHP flow temps is on the low side. Unless you have a lot of rooms, it also suggests multiple rads in each room. And then there is all the pipework to supply those rads. Maybe that is why your installer 'played safe' and went for an OTT circulating pump. Furthermore, a 12kW Midea heat pump doesn't give you 12kW when you need it, probably more like nine point something. On the numbers, your house will be cold in cold weather. As a bench mark, my heat loss is 12.4kW, my heat pump is 14kW, and it starts to struggle at zero degrees ambient and below. In the December cold snap, the main living rooms were 2-3 degrees below design temps. When it's milder, it manages just fine.

Posted by: @filipeI feel I need to understand the relationship between the input flow/return and output flow/return temperatures to better understand that side of the system.

Your language here is a bit confused. There isn't really anything such as an input flow let alone input flow/return. Normally the reference point is the heat source (in our case a heat pump) and the water flows from it, goes round the house, and then returns to it, giving us the terms flow and return, and thereby flow and return temps. These are also sometimes referred to as LWT (leaving water temp) and RWT (returning water temp). Water heated by the heat pump leaves the heat pump, goes round the house delivering heat energy, and cooling as it does so, and then returns as a cooler temp to the heat pump which reheats it.

The temperature difference between the flow and return temps (or LWT/RWT) is fundamental to how any heating system works. It is often referred to as 'delta t' and for heat pumps is conventionally around 5 degrees. The reason why it is so fundamental is because the heat energy delivered to the house is determined by a simple equation: kWh delivered = flow rate of fluid (given as volume over time, not speed) x specific heat of circulating fluid (how much heat the fluid can hold, it varies) x delta t (the bigger the temp drop, the more heat has been transferred). This means there is a simple linear relationship between delta t and heat delivered - double the delta t and you double the heat delivered, halve the delta t and you halve the heat delivered.

This delta t (between flow and return) is not the same as another important delta t, the delta t between the mean rad temp (usually assumed to be half way between the flow and return temp) and the room temp. This delta t determines how much heat is transferred from the rad to the room. For older fossil fuel systems, this delta t was often actually or assumed to be 50 degrees, meaning even a small rad could deliver quite a lot of heat. At heat pump flow/return temps, this rad/room delta t is considerably less, maybe 30 degrees or often even less, so the same size rad delivers less heat, meaning you need larger rads to deliver the same amount of heat. Very roughly, all other things being equal, moving the rad/room delta t from 50 to 30 degrees means you will need rads that are twice as large. Only if your old rads were considerably oversized will you avoid the pain and cost of new larger rads. If you have a fossil fuel boiler, it is possible to test whether you will need new rads empirically (I think you have done this) while you still have the old fossil fuel boiler, by running it at heat pump temps and seeing whether the rooms get up to design temps. If they do, your existing rads are OK, if they don't, you need new larger rads.

The other big factor in all this is heat pump efficiency is very dependent on flow temp (LWT): the higher the LWT, the less efficient the heat pump. This in turn leads to a drive to keep the LWT as low as possible, which in turn means the rad/room delta t is lower, meaning even bigger rads, until you give up sticking the blighters on the walls and instead bury them in the floor - huge 'radiators' that can work with an even lower delta t, only we now call it under floor heating.

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Posted by: @cashbackThe Shelly is supposedly accurate to +/-1% on average (the accuracy increases with the power.

I expect the Shelly is measuring the actual power and the V * I output is apparent power.

Once you solve the "sample and hold" behaviour of the heat pump interface, you should [if not already] adjust for the power factor of your heat pump. Though this will likely increase the gap between the shelly data and your heatpump data rather than reduce it.

Posted by: @william1066Posted by: @cashbackThe Shelly is supposedly accurate to +/-1% on average (the accuracy increases with the power.

I expect the Shelly is measuring the actual power and the V * I output is apparent power.

Once you solve the "sample and hold" behaviour of the heat pump interface, you should [if not already] adjust for the power factor of your heat pump. Though this will likely increase the gap between the shelly data and your heatpump data rather than reduce it.

This is rather too cryptic for me, how, for example, would I 'solve the "sample and hold" behaviour of the heat pump interface'? I know you are replying to @cashback but I and I expect everyone else trying to monitor their heat pump has the same fundamental problem, the heat pump data reporting is wrong.

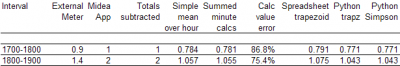

Instead of a Shelly, I do have an external Class 1 / B kWh energy meter that supplies only the heat pump, and I plan to compare its kWh readings over time with those calculated from the heat pump data to see if I can determine whether there is a constant difference which I can factor in as a correction factor. From past rather crude measurements, I suspect there isn't, instead, the error varies over time. Here's very limited (only covers two hours) data from a few days ago, numbers are kWh (except error column) over the hour from various sources/methods (from left to right: external meter, Midea app hourly data, current lifetime kWh minus lifetime kWh one hour ago, and then various ways of treating volts time amps over the hour). Interestingly, the 'sophisticated' area under the curve methods were actually slightly worse than the simple methods. The Riemann sum, when I finally got one, was just as bad, if not worse (the sample hour was a different one, so it doesn't fit in this table, but the simple calculation methods gave 2.48 to 2.49 kWh, the python methods gave 2.44 kWh, but the middle (left and right were way out) Riemann sum was hopeless, 2.11 kWh; unfortunately I don't have the external meter readings over that hour). As you can see, the calculated values are wrong, but the error isn't constant. Over those two hours, the calculated values under-reported energy in, implying COP based on them would be falsely high, which works to the manufacturer's advantage:

The obvious solution for energy in is to ignore the heat pump data altogether, and just use the external meter, but I have yet to set up optical (LED) pulse count monitoring over modbus, so I have to get the numbers manually. The problem is how to get an accurate energy out figure without going to the expense and trouble of fitting third party flow rate and temp sensors, which are themselves not without accuracy and other problems.

If heat pump manufacturers are going to make performance data available, why the heck can't they say how they get it, and what the accuracy is? They must know the answer to both these questions, so why be so coy? Are they sitting on compressorgate, hoping it will go away?

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Posted by: @cathoderayThis is rather too cryptic for me, how, for example, would I 'solve the "sample and hold" behaviour of the heat pump interface'?

I am not sure how you do this for your heat pump. I had the same issue on the Samsung when I did not follow the instructions on how to setup the modbus interface "properly". This situation is specific to the Samsung modbus add on module.

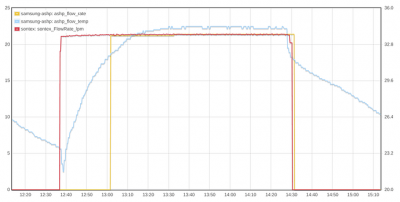

See image below taken from Glyn Hudson's post on his open energy monitor site for the resulting behaviour.... a significant lag in the flow rate data. This was fixed by Glyn and me [independently] as per my post on that forum, copied below. This will likely NOT be the solution for your situation though.

Posted by: @cathoderayI have yet to set up optical (LED) pulse count monitoring over modbus, so I have to get the numbers manually.

In home assistant, this is literally a 20min job (assuming you can power your esp32 where your pulse meter is).

The specific config for my heatpump power meter is as below. I am using the openenergy monitor pulse counter, which works brilliantly and ran a PoE cable to my esp32 as I don't have a suitable power socket in my meter cabinet..

- platform: pulse_meter

pin:

number: 4

mode:

input: true

pulldown: true

unit_of_measurement: 'kW'

name: 'Heat Pump Power'

id: heat_pump_ss_power

device_class: energy

state_class: measurement

accuracy_decimals: 3

filters:

- multiply: 0.012

total:

name: "Heat Pump Total Energy"

unit_of_measurement: "kWh"

state_class: total_increasing

device_class: energy

accuracy_decimals: 6

filters:

- multiply: 0.0002

Posted by: @william1066This will likely NOT be the solution for your situation though.

This is why I am now trying to be as generic as possible in what I do, the idea is to have a generic approach that can be used either as it is or with minor tweaks (eg for a Samsung unit you need to add the modbus interface) to monitor and optionally control a heat pump. I want to be able to say if you have a modbus interface, and access to the register addresses, then this is what you can do.

There is no manual per se for what I am doing apart from the modbus register tables, so there are no instructions to follow (or not follow).

When you say "After writing as directed in the manual, I seem to be getting [near] real time data from the flow sensor" I find myself confused. As I understand it, modbus is a two way connection, you can either write to, or read from, the device. The two are opposite but complimentary: you either set the data, or get the data. But in your description, you seem to be saying you need to write (to multiple addresses all at once) to be able to read (a single address). This makes it seem as if you are both writing (setting) and reading (getting) at the same time, which doesn't make sense to my weak and feeble brain.

So far I have managed to avoid ESPs, basically because they add a layer of complexity I don't need. 22 lines of not very human readable code ("pulldown: true"? "filters: multiply: 0.012"?) is again not very beginner friendly. The modbus cable I am using (FTP, Foil shielded Twisted Pair ethernet cable) has currently unused cables in it so I can get the USB 5V to any device I connect to the modbus cable. The external meter I have (an Eastron SDM120) does have an electrical as well as LED pulse output but unfortunately it is not the SDM120M model where the M suffix indicates it has modbus output. I am looking for a gadget that will turn my SDM120 into a SDM120M ie a gadget that will take the pulse output and translate it into modbus which I can then read over the wire. If all else fails, I suppose I could physically replace the SDM120 with a SDM120M, but again that is hassle and expense I would rather avoid.

If/when I get this set up, I will only need two lines of code, one the read the modbus register, and one to write the data to my CSV file, plus maybe an intermediate line to do some calculation on the data, depending on how it actually arrives.

It is possible it may be even simpler. The modbus setup I have is sent using RS-495, maybe all I need is something that will convert the pulsed output to RS-485. I am going to email Eastron to see if they have any suggestions.

Throughout, I am as ever these days guided by the twin principles of simplicity and generalisability. I want anything I suggest to be doable by an 'normally intelligent, normally capable and normally willing' beginner.

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Posted by: @cathoderayAs I understand it, modbus is a two way connection, you can either write to, or read from, the device. The two are opposite but complimentary: you either set the data, or get the data. But in your description, you seem to be saying you need to write (to multiple addresses all at once) to be able to read (a single address).

I understood it differently.

I thought @william1066 was describing that you must first configure several aspects of the device, but that you can't do each separately.

Instead you have to use the Modbus command to write to several registers at the same time.

Having done that, you are then able to read the data you're after.

Save energy... recycle electrons!

@transparent - it's probably just another case of bad manual language. I thought modbus 'functions' were used to tell it what to do eg 03 means 'read multiple holding registers' eg in miminalmodbus (a python module) there is this:

read_register(registeraddress: int, number_of_decimals: int = 0, functioncode: int = 3, signed: bool = False) → Union[int, float][source] Read an integer from one 16-bit register in the slave, possibly scaling it. The slave register can hold integer values in the range 0 to 65535 (“Unsigned INT16”). Args: registeraddress: The slave register address (use decimal numbers, not hex). number_of_decimals: The number of decimals for content conversion. functioncode: Modbus function code. Can be 3 or 4. signed: Whether the data should be interpreted as unsigned or signed.

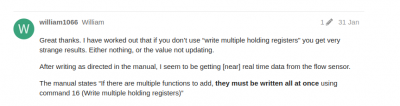

The third argument (functioncode, defaults to 3) means 'read multiple holding registers' (even though only one is read...). The quote from the Samsung manual doesn't really make sense: "The manual states “If there are multiple functions to add, they must be written all at once using command 16 (Write multiple holding registers)”". You can't add functions, you, or rather modbus does functions, and 16 (Write multiple holding registers) isn't a command, it's a function.

But the thing is, as I understand it, @william1066 is trying to read a register, specifically the flow [rate] sensor. Why all the palaver about some apparently arbitrary writing to registers (which may well screw something up) when all your want to do is read something?

More pointless complexity, no doubt introduced to make sure we live in interesting times.

Link to the Glyn Hudson page/post here (<=link).

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

Reading the information from Schneider, who bought Modicon, who originally developed Modbus, it is open source, so can be changed from the original format by developers.

It is my understanding that there can only be 1 Client (Master) and up to 247 Servers (Slaves) on any individual system.

Communication can only be initiated by the Client, not by any of the Servers, so a read data function would be initiated by the Client issuing a request, and the relevant Server responding to that request.

The relevant Function Codes are detailed below in the document.

https://www.se.com/us/en/faqs/FA168406/

The 'issue' with Modbus is the lack of conformity.

A couple of weeks ago I was comparing two Battery BMS units from different manufacturers.

One of those manufacturers doesn't use an address/ID in their Modbus packets.

The BMS requires a separate RS485 connection to the controller for each unit.

Samsung will no doubt have their own 'standard', and may well be using the term 'functions' in a manner which suits themselves. 🤔

Save energy... recycle electrons!

Not so long ago a likened the hardware and RS-485 to the Morse keypads and telegraph wires in an old telegraph system and modbus to the Morse code sent across the telegraph system as a way of getting my head round what is what.

It is not a perfect analogy because modbus does indeed have one master and potentially hundreds of slaves and as one would expect the master is in charge, and the slaves do what they are told. It is also a serial system, the slaves are bound serially by a single chain (cable), like slaves in a hideous slave chain. For some bizarre reason, the last slave usually has a 120 ohm resistor strapped across his ankles.

Each slave has a unique identity, or address, so the master can chose which slave to communicate with by using that unique address. But the language is rather limited. All the master can do is either tell the slave to do something, or ask the slave what it is doing. The something can be binary eg grin/don't grin (heating on/off), or a numerical value eg walk at this speed (flow rate, only units are volume/time eg litres per minute not distance/time eg metres per second) . In modbus terminology, telling a slave to do something is called writing to that slave, and getting the slave's state is called reading that slave. And that is about it, apart from all the other hideous complexities introduced by those who would have us live in interesting times.

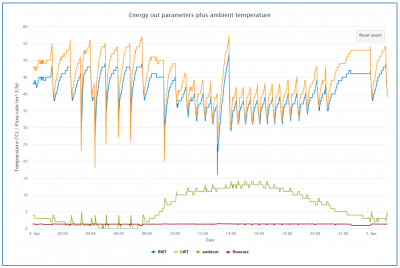

Given this basic setup, there is no need for modbus to be complex, and that's why I like minimal modbus (the python module) because it truly lives up to its name, a minimal but still human readable modbus interface for python. All you have to do is set the modbus parameters (baud rate, which is how fast the communication is, and various other parameters), name the slave, and then read or write to register addresses. It really is that simple. If you do it over a copper wire connection rather than wifi, it stays simple (two wires) and robust. Putting all this together, I think I can say that it is suitable for a normally intelligent, capable ('screwdriver-ready') and willing beginner. It is also very affordable. As long as your heat pump has a modbus connection unsullied by the likes of Samsung, one bit of hardware, the bi-directional RE-485 to USB converter, one length of cable (the right sort of ethernet cable works), that 120 ohm resistor and some very basic python code, and you are ready to go. You can then view the data in Highcharts JS. Here are my energy out and ambient temp parameters for the 4th April (chosen because it has a range of ambient temps):

On the left hand side, early hours of the morning when it was cold outside, you can see larger delta t values (difference between LWT/RWT) and rather a lot of defrost cycles (deep dives where the LWT gets to be cooler than the RWT, and corresponding little peaks in ambient, as the heat pump kindly heats up my garden). In the middle and early right hand side daytime period you can see reduced LWT/RWT and delta t values (the heat pump lowering its output as it gets warmer outside, this is the weather compensation at work), along with a big 1300 spike which is the heat pump switching to heating my hot water, and on the extreme right hand side you can see the LWT/RWT and delta t all increasing as it gets colder outside (weather comp at work again). You can also see how little the flow rate varies (as discussed elsewhere on the forum: heat pumps mostly don't use variable flow rate to regulate output).

Nothing in this post is beyond the normally intelligent, capable and willing beginner.

Midea 14kW (for now...) ASHP heating both building and DHW

The 120 Ohm resistor at the end of the transmission line is to prevent signal reflection.

When power is first applied to a transmission line, a waveform flows along the line as it charges up. If this waveform hits an open circuit at the end of the transmission line, it is reflected back, and in fact could sit on top of the now charged line, thereby almost doubling the voltage, until the waveform dissipates.

When transmission is taking place, power is continually being switched on and off, to create the data signal which flows along the line. If this data signal were to hit an open circuit at the end of the line, it is quite possible that the reflection would corrupt the present signal, and cause a data transmission failure.

For those old enough to remember, an analogue TV aerial was connected using 75 Ohm co-axial cable, the Modbus system was developed to use 120 Ohm nominal impedance, twisted pair instrument cable. Hence the need for a 120 Ohm termination resistor.

- 27 Forums

- 2,495 Topics

- 57.8 K Posts

- 359 Online

- 6,220 Members

Join Us!

Worth Watching

Latest Posts

-

RE: Solis inverters S6-EH1P: pros and cons and battery options

@jancold I only discuss data.. Fogstar were not impress...

By Batpred , 11 minutes ago

-

RE: What determines the SOC of a battery?

@batpred Ironically you didn't have anything good to...

By Bash , 45 minutes ago

-

RE: Testing new controls/monitoring for Midea Clone ASHP

Here’s a current graph showing a bit more info. The set...

By benson , 59 minutes ago

-

RE: Setback savings - fact or fiction?

True there is a variation but importantly it's understa...

By RobS , 59 minutes ago

-

Below is a better quality image. Does that contain all ...

By trebor12345 , 1 hour ago

-

Sorry to bounce your thread. To put to bed some concern...

By L8Again , 1 hour ago

-

@painter26 — they (the analogue gauges) are subtly diff...

By cathodeRay , 2 hours ago

-

RE: Electricity price predictions

I am always impressed with how you keep abreast of so m...

By Batpred , 3 hours ago

-

RE: Humidity, or lack thereof... is my heat pump making rooms drier?

@majordennisbloodnok I’m glad I posted this. There see...

By AndrewJ , 3 hours ago

-

Our Experience installing a heat pump into a Grade 2 Listed stone house

First want to thank everybody who has contributed to th...

By Travellingwave , 6 hours ago

-

RE: Struggling to get CoP above 3 with 6 kw Ecodan ASHP

Welcome to the forums.I assume that you're getting the ...

By Sheriff Fatman , 9 hours ago

-

RE: Say hello and introduce yourself

@editor @kev1964-irl This discussion might be best had ...

By GC61 , 10 hours ago

-

RE: Oversized 10.5kW Grant Aerona Heat Pump on Microbore Pipes and Undersized Rads

@uknick TBH if I were taking the floor up ...

By JamesPa , 1 day ago

-

RE: Getting ready for export with a BESS

I would have not got it if it was that tight

By Batpred , 1 day ago

-

RE: Need help maximising COP of 3.5kW Valiant Aerotherm heat pump

@judith thanks Judith. Confirmation appreciated. The ...

By DavidB , 1 day ago

-

RE: Recommended home battery inverters + regulatory matters - help requested

That makes sense. I thought better to comment in this t...

By Batpred , 1 day ago

-

Bosch CS5800i 7kW replacing Greenstar Junior 28i

My heat pump journey began a couple of years ago when I...

By Slartibartfast , 1 day ago

-

RE: How to control DHW with Honeywell EvoHome on Trianco ActiveAir 5 kW ASHP

The last photo is defrost for sure (or cooling, but pre...

By JamesPa , 1 day ago

-

RE: Plug and play solar. Thoughts?

Essentially, this just needed legislation. In Germany t...

By Batpred , 1 day ago

-

RE: A Smarter Smart Controller from Homely?

@toodles Intentional opening of any warranty “can of wo...

By Papahuhu , 1 day ago

-

RE: Safety update; RCBOs supplying inverters or storage batteries

Thanks @transparent Thankyou for your advic...

By Bash , 1 day ago

-

RE: Air source heat pump roll call – what heat pump brand and model do you have?

Forum Handle: Odd_LionManufacturer: SamsungModel: Samsu...

By Odd_Lion , 1 day ago

-

RE: Configuring third party dongle for Ecodan local control

Well, it was mentioned before in the early pos...

By F1p , 2 days ago