I’ve been participating in a Policy Fellowship with the Royal Academy of Engineering, focusing on the value of heat flexibility and, crucially, the means of delivering it. To grasp the advantages and disadvantages, I experimented with some heat flexibility using my heat pump, now in its second winter season.

For this, I use Octopus Energy’s Agile tariff for my heat pump operation. This tariff, unfamiliar to some, is tied to the wholesale price and fluctuates every half hour. Initially, I set my Ecodan heat pump to timed adaptive control, incorporating an off-period from 4 pm to 7 pm during peak price times – a process requiring no expert energy knowledge. However, since the start of this heating season, I’ve progressively advanced the controls.

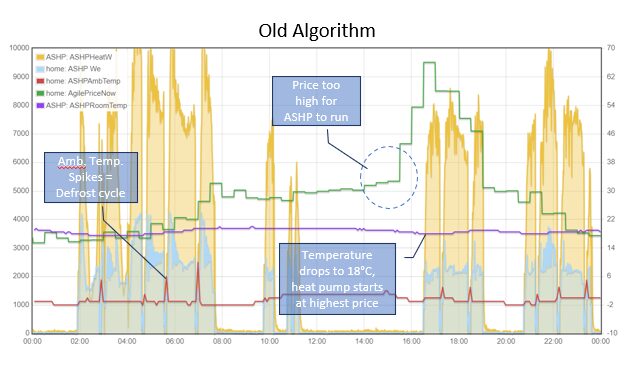

I programmed a script to lower the heat setpoint to 18°C whenever the Agile tariff exceeded 30p/kWh. Then, to my dismay, during a cold November week, we experienced a Dunkelflaute event. The Agile price soared above 30p/kWh for most of the afternoon, resulting in my heat pump operating during the three most expensive hours of 2023 (see Chart – Old Algorithm).

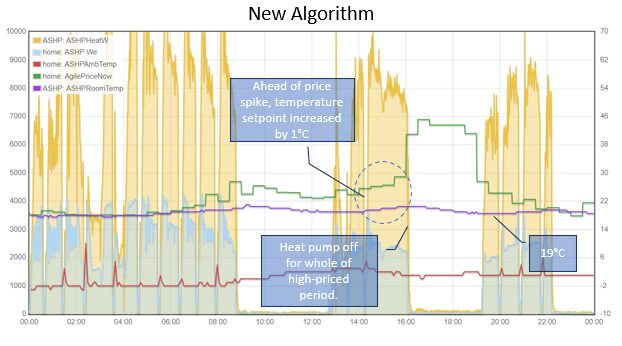

I wrote additional code to retrieve the Agile tariff an hour ahead and incrementally boost the room temperature setpoint by 0.5°C, inversely proportional to the ambient temperature. Then, when the actual peak period begins, the temperature setpoint is lowered to 18°C.

Finally, I fine-tuned the peak period to identify the six most expensive half-hour intervals in the morning and afternoon. I programmed the system to pre-boost before these periods and reduce the setpoint during them.

All of this has worked quite well, and with the boost, even on cold days, the temperature in my front room rarely drops below 19°C. As you can observe in the chart (New Algorithm), on a day when temperatures were around freezing, the room temperature dipped to 19°C. This clearly depends on how well insulated and draft-proofed your house is, but it perhaps indicates that there is additional value to be gained from better insulation, beyond just reducing the thermal input required to maintain a comfortable temperature.

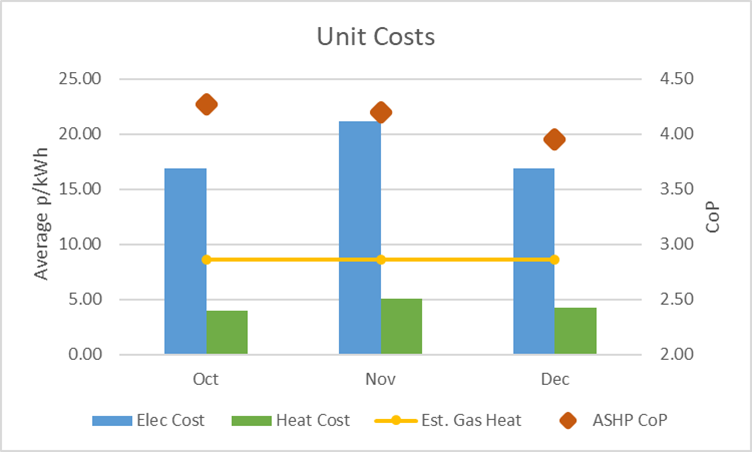

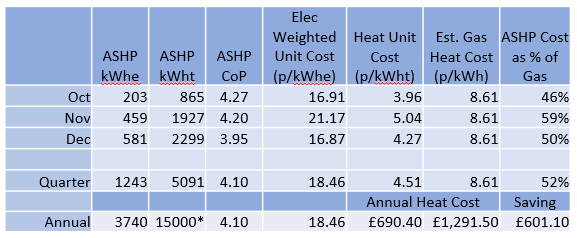

So, what has been the impact on my bills? As the figures show, despite some underperformance in November, my heat pump has operated at 52% of the cost of providing the same amount of heat with a gas boiler. I believe that if my algorithm had been more precise from the start, the cost could have been halved – let’s see what a full year of data reveals. (For the gas cost calculation, I used the ‘Flexible Octopus’ gas tariff, assumed a boiler efficiency of 87%, and distributed the standing charge (£100/annum) across 15,000kWh, which is my typical historical gas usage.)

Annually, this translates to a saving of £600, assuming the sCoP remains at 4.1 (which it achieved last year). It’s worth noting that I’ve conservatively estimated the same heat input from my heat pump as the gas used by my boiler, based on the assumption that the house will be, on average, warmer and thus incur slightly higher losses. To put it in government terms, if half of UK homes could adopt this approach, it would result in consumer savings of £7.92 billion per annum.

In reality, this approach would also offer broader system benefits. It could enable early deployment of heat pumps before network reinforcement is complete, as peak demand can be reduced. Additionally, it could help lower the required capacity for our future ‘Dunkelflaute’ generation (whether that be unabated gas, hydrogen power, or some yet-to-be-developed solution), allowing that capacity to operate at a higher load factor, thus reducing the unit cost.

However, we cannot expect consumers to manage this alone. Electricity suppliers need to step up with their offerings. They should collaborate with heat pump installers to ensure that this technology is integrated during the installation of heat pumps. Moreover, appropriate regulatory frameworks are needed to enable these developments for the broader populace.

Hi Rachel, what a great piece of work and inspiring too.

Since I have no coding skills I was planning to rely on a tariff such as Cosy and battery storage to ensure minimal usage during the peak period. But that means another battery and hence more capital expenditure.

You’ll obviously be aware of several heat pump geeks who programme their home assistant to do similar tasks. Is looking at that within the terms of your Fellowship?

Have you asked other on-line communities for similar comparisons to their previous fossil fuel use? Can they be verified? Great piece of work, and I hope appropriate decision makers can understand it!

Good piece of work.

As you discovered chasing cheaper tariffs does not always align with the weather conditions.

Some of my previous ideas have been, like you, to boost the indoor temperature during the often warmer afternoon period when a heat pump would be operating at a higher efficiency, which would be particularly beneficial with solar PV helping to provide some if not all of the electrical energy.

The use of some form of thermal store, be that a large concrete slab with UFH, or storing thermal energy in a sufficiently large quantity of water.

I fully agree with your sentiment of better insulation to reduce energy consumption, I can’t remember how many times I have said “If you don’t need the electrical energy in the first place, then it is not necessary for it to be generated and transmitted"

Has any of your group thought of using solar thermal to provide energy in a thermal store, which could be used to replace or supplement a heat pump during the peak tariff periods? A further idea that I proposed quite some time ago was to store solar thermal produced energy, again in a water based heat store, but then use the stored energy to pre-heat the air being supplied to a ASHP during the colder periods of the day, thereby increasing the overall operating efficiency.

I have not yet convinced ‘she who must be obeyed’ to replace our gas boiler with a heat pump. To do our bit for the environment and help save the planet I had solar PV installed over 10 years ago, which reduced our electrical energy consumption by approximately 50%. A couple of years back I did manage to get an Air to Air (A2A) heat pump past the ‘approvals committee’, which I now use to supplement the gas boiler when sufficient solar PV generation is available. It is particular useful during the shoulder months and cooler Summer days, when the A2A is used to boost the indoor temperature during daylight hours, by a sufficient amount to not require any additional form of heating during the rest of the day, other than my ‘hot body’ of course. 😋 My goal is to to also reduce our gas consumption by approximately 50%.