We’re almost old-timers amongst PV (photovoltaic) users, as we used to live in a zero carbon house in Kent that had a 4kW PV array, but no storage, and we also have a holiday home in South Africa to which we added a PV system with batteries. The Kent property had the PV inverter hidden in the roof space and there was no monitoring whatsoever. The Immersun immersion diverter self-destructed spectacularly, just months after the company ceased to trade, and was replaced with a myenergi Eddi. The feed-in tariff of 17p/kWh returned £500 per year, regardless of self-consumption, so we were reasonably satisfied despite the limitations of the system.

We moved to the new build property, in Suffolk, in September 2020. This comprised 478sqm over two floors, with underfloor heating throughout, an 18-zone Honeywell evohome system and an oil-fired boiler. With an estimated annual bill for electricity and oil of £2,500, we decided to make a priority of going green. We needed a retirement project, after all.

£2,500 is also the figure we were spending in Kent, although with heating and hot water supplied by a biomass boiler (great in principle, but a pain in practice). Our lofty aim was to halve that by maximising the use of PV generation with battery storage, alongside feed-in-tariffs and replacing the oil-fired boiler with an air source heat pump. We also now had two EVs to throw into the mix.

The property is a converted filter house that formed part of an Anglian Water pumping station. The original section was built in the ’50s, with thick brick walls and a reinforced concrete roof that once had water cascading over it. The new section is constructed using a system of insulated concrete forms (ICF), which provide strength, airtightness and insulation. High performance glazing is used throughout and there’s plenty of solar heat because of the south-easterly aspect. We’ve added Prestige 50 window films to retain heat and prevent sun damage to fabric.

We commenced our search for a PV system installer shortly after moving in. We also had to sort out the incorrect binding of the evohome controller, which had been bodged by the builder, resulting in some rooms heating up to a sweltering 27C and the system refusing to turn off. It proved difficult to find a heating engineer who knew the system and would touch someone else’s work.

Finding a PV installer also proved more problematic than we expected – and complicated by Covid restrictions. One installer recommended holding off adding a battery until we’d evaluated the impact of PV generation. Another carried out a comprehensive survey but wouldn’t be tied down to any one inverter and lost interest when we questioned his specification. Two installers carried out desktop surveys but never took things further.

The installer we eventually chose was keen to promote “the equipment I like to use” and his price was keen enough for us to accept that. The fact that he was registered with the Flexi-Orb scheme rather than MCS didn’t raise any alarm bells, either. It must have been the smart suit and easy small talk that persuaded us.

The final specification was for 18 QCell 315W panels with micro inverters, a SolarEdge 3680 HD wave inverter with integrated EV charging, a GivEnergy 3kW AC coupled inverter, two GivEnergy 5.2kWh batteries (which I’ve reviewed here) and a SolarEdge hot water controller.

We decided to mount the PV panels on the smaller flat roof because it was easier to make the necessary structural calculations for reinforced concrete than for the atypical materials used in the new roof. A small perimeter of brickwork completely hides the panels from view, even when someone is walking along the field opposite the house. The pitch of the panels is 10 degrees, so output will be less than 5.6kWp unless the sun is overhead.

The logical position for the inverters and batteries was the garage, although this is 20m away from the plant room where the hot water controller was to be installed. The specs for the controller mentioned RF communication of up to 50m indoors and 400m outdoors, but this proved to be woefully inaccurate, although, to be fair, there was ICF in the way.

A considerable amount of toing and froing with SolarEdge support followed, including false starts and unnecessary expense, with an eventual solution of two SolarEdge ‘smart’ sockets being used as extenders. This seemed a bit of a kludge, but both SolarEdge and our installer were unrepentant. People in ICF houses shouldn’t expect to communicate, I guess.

Something we hadn’t reckoned on was the hassle of getting different manufacturers’ equipment to play ball with each other, not to mention the irritation of multiple portals for hardware monitoring. Although any battery should charge from any inverter, monitoring relies on CT clamps being positioned correctly. Unfortunately, plugging in the integrated EV charger gives the GivEnergy portal the impression that there’s an extra 3.6 kW of PV generation happening, as there’s no way of putting the CT clamp in the right place inside the SolarEdge inverter case. Neither SolarEdge nor GivEnergy were able to come up with a solution, and, once again, our installer showed no regret for inadequately researching the hardware he was selling. Fortunately, functionality hasn’t suffered, although our patience has taken a nosedive.

Probably our biggest gripe with the system stems from the installer being certified with Flexi-Orb rather than the industry standard MCS. Although Octopus did originally accept Flexi-Orb certification, this ceased in April 2020, i.e., six months before the installer sold the system to us, and when we mentioned wanting to use the Outgoing Octopus tariff. His suggestion was to change electricity supplier. Cue much indignation, gnashing of teeth and generally not being amused.

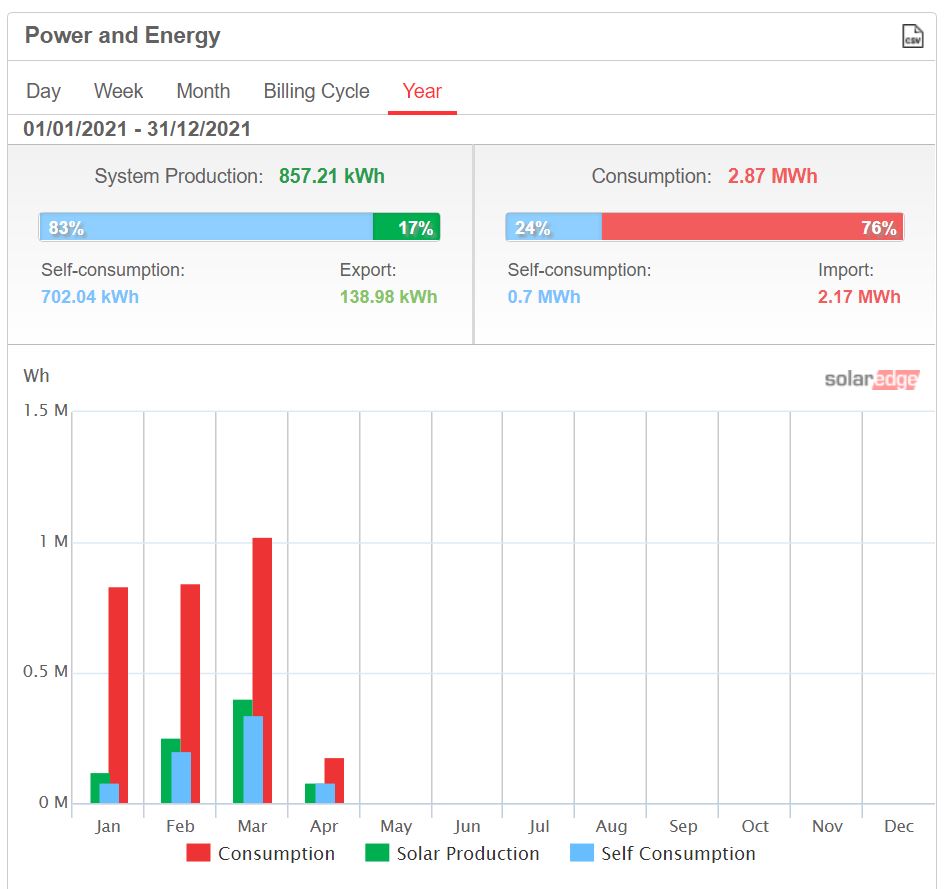

Since having the PV system installed, our electricity consumption has remained at around 220 kWh per week. If we hadn’t been in lockdown and driving more, this figure would been considerably greater. But 24% of our consumption is now self-generated and our electricity bill has dropped from £140 per month to £70 per month, which means that using the Agile tariff to store electricity when the price is low has really paid off. The self-consumption figure is better than we anticipated for winter months and we expect to see bigger gains over the spring and summer, albeit without being reimbursed for exported electricity. We live in hope of Flexi-Orb and Octopus resolving their differences.

And ending on a positive note, the immersion controller seems to work well, topping up the hot water using the PV excess, although it tends to go off piste occasionally and divert power when it’s dark. SolarEdge support say they’re monitoring the situation.

Next stop, an air source heat pump…

Does the Prestige 50 window film change the colour of the windows/glass?

Yes, it adds a light grey tint but it’s hardly noticeable.

Thanks David. And I assume these films assist with keeping heat in, preventing it from escaping.

It’s meant to do a bit of everything, I think. The specs are here: 49% visible light transmission, 42% solar energy reduction, 46% glare reduction, 99% UV reduction.