The shift towards environmentally-friendly heating technologies is a critical aspect of current sustainable development efforts. Heat pumps have been recognised for their potential to contribute to energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. Nonetheless, new data suggests there may be considerable differences in efficiency and cost between high-temperature heat pumps and those operating at lower temperatures. A thorough review of a slide from an environmental consultant reveals significant findings pertinent to this discussion.

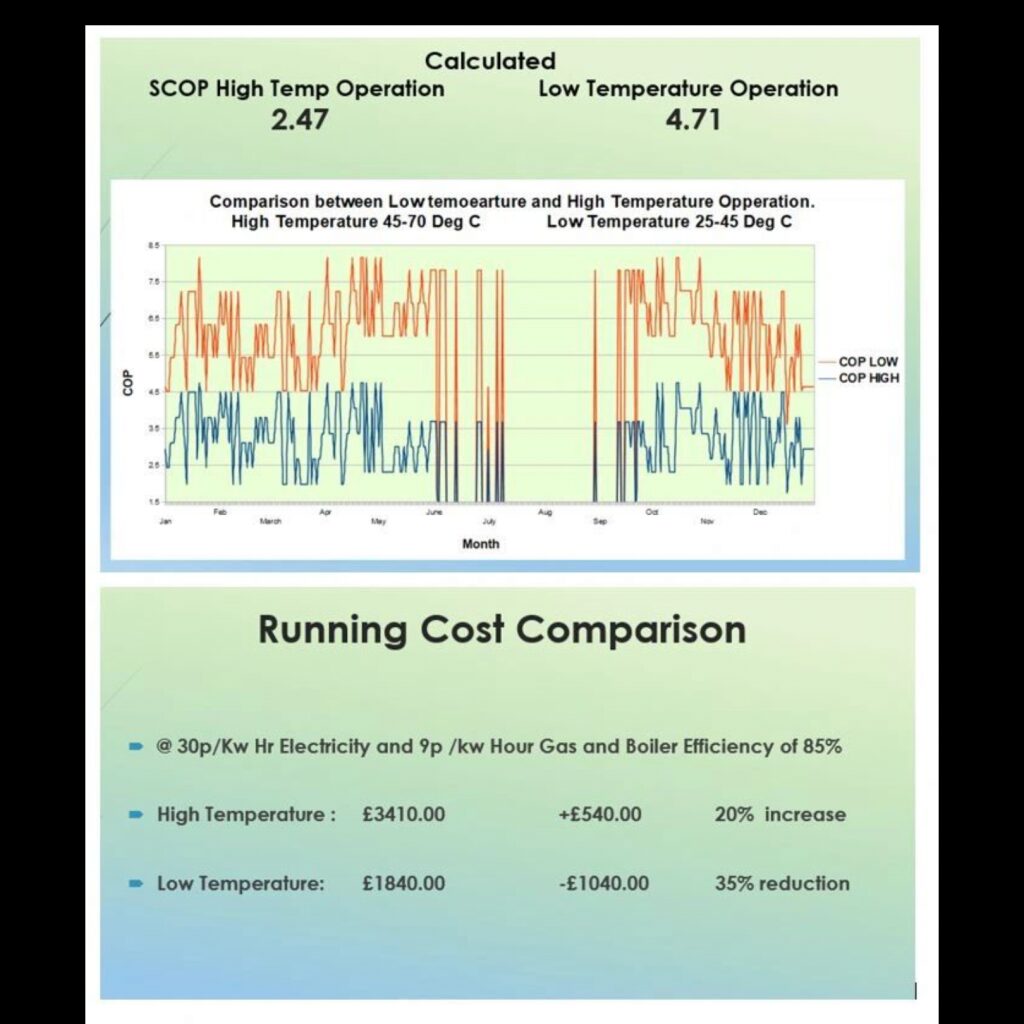

The slide in question, based on data from Sune Nightingale’s last year’s hourly temperature figures, contrasts the running costs and efficiency of a high-temperature heat pump system — operating without system upgrades on weather compensation from 45 to 70 degrees Celsius — against a well-designed system operating between 25 and 45 degrees Celsius.

A closer examination reveals that the Seasonal Coefficient of Performance (SCOP) for the high-temperature operation stands at a lower 2.47, as opposed to 4.71 for the low-temperature operation. The Coefficient of Performance (COP) directly correlates with the heat pump’s efficiency: the higher the COP, the more efficient the system. Thus, the data unequivocally points to the superior efficiency of the low-temperature heat pump.

This efficiency translates into significant cost savings. According to the slide, the annual running cost for the high-temperature heat pump is £3,410, whereas it drops to £1,840 for the low-temperature system, marking a 35% reduction in costs. This is not just a matter of improved efficiency but also reflects on the substantial economic benefits of a system designed for lower operating temperatures.

The slide also hints at the importance of system design. It suggests that incorporating elements like buffer tanks or system separation, which are often part of high-temperature heat pump systems, could further degrade performance.

The revelation presented in the slide is striking. As manufacturers launch high-temperature heat pumps with considerable marketing efforts, the data cautions potential buyers and industry professionals. It implies that, without a meticulous approach to the system design and consideration of operating temperature ranges, high-temperature heat pumps may not be the optimal choice either economically or environmentally.

The evidence, to my mind, is clear: high-temperature heat pumps, despite their popularity and aggressive marketing, may not always be the best path forward. As the industry strives for greener solutions, the focus must shift towards optimising system design and operational parameters to ensure that heat pumps deliver on their promise of efficiency and cost-effectiveness. This slide serves as a stark reminder that, in the realm of sustainable heating, more heat does not necessarily equate to better performance.

What we really need is the levies moving off electricity and onto gas…

I would be interested to know what you feel is high-temperature too, Brendon.

I agree with both of you in different ways.

To me, HT heat pumps are a somewhat quick-n-dirty fix to allow a HP to replace a boiler (ish), with minimal re-working of the house side. They will self-evidently be less efficient than a LT heat pump + good system design, therefore they will cost more units of electricity to run.

If the tariffs stay as they are, the HT “quick fix" approach will cost more than gas to run. with tariffs as they are, only an LT pump + good system design + engineering saves money over gas. (PV + storage batteries can help too but leaving that aside for the moment)

So no-one with more sense than money would be putting in a HT system and planning to run it at HT forever.

But is the argument below also valid?

If the tariffs were reduced so that the run cost of the HT pump is less than gas, then the pure HT approach becomes viable economically for the “typical end customer". Due to not re-engineering the house side, they could perhaps be fitted more quickly with less disruption, and by less expert people , and thus get more done per year. Therefore on the large scale, moving the country faster towards where we want to be. which is what matters.

later on , whenever there’s a feasible opportunity in terms of the house’s use and users, they can of course refit to run at LT and save some more run cost – if they want to.

questions:

with lots of HT systems, what then happens to the electricity generation and distribution side ? do all these inefficient HT systems blow the grid? do we burn more gas to generate the electricity to run the HT systems than we would have done by just burning the gas in the house?

Do HT systems cope better with low flow rates and high DT that would be expected in a system that’s running currently with a boiler? as that’d be a necessary condition for a “minimal remove and replace" approach. or are they the same as LT?

Exactly that. There is clearly an argument, in some, perhaps many retrofit situations with radiators, for running at say 55C ((which I guess is on the cusp). It depends on the specific house and the specific priorities. There is also an argument for running the DHW cycle at (say) 65C, which is exactly what Vaillant do with their R290 pumps – no use of the immersion even for legionella. A rebalancing of the tariffs makes heat pumps more accessible which hastens the change to low carbon heating which is necessary. So I dont think it should be ruled out.

I think its telling that the new building regs specify max design flow temp (even for gas) =55C. Somebody, somewhere, has worked out that this might be a sweet spot balancing capital cost of retrofitting a heat pump with running cost, particularly as the latter rebalances between gas and electricity.

Im certainly not going to advocate running a heat pump at 65C for space heating, but 55C for space heating and 65 for DHW isn’t silly. Lower running cost (larger emitters) can then be offered as an optional upgrade.

@JamesPa

I think that you will find the 55C for gas boilers is to ensure condensing takes place, and if the gas boiler is to be replaced at some time in the future with a heat pump, then to avoid further system changes then the system needs to be able to operate at no higher than 55C whatever the heat source.

Er is that true, or is it only the case that any heat pumps when run at high temperature results in lower efficiency (which is of course the case)? Two different questions. There are reasons for ‘high temperature’ heat pumps other than their ability to run at high temperature.

I think, sadly, you can cross out ‘high temperature’ in this sentence!

The original text looks like a piece of marketing blurb by a company that doesnt yet have an R290 heat pump, or alternatively by someone paid to rubbish heat pumps (there is plenty of that going on). Several manufacturers seem to be combining a transition to R290 with better sound performance and aesthetics, but then marketing the result as a ‘high temperature heat pump’. I guess that, a manufacturer that has chosen not to take this route may wish to confuse matters with imprecise information.

Of course it is true that the focus must shift towards optimising system design and operational parameters to ensure that heat pumps deliver on their promise of efficiency and cost-effectiveness, whilst at the same time being mindful of practicalities particularly in a retrofit situation. So I very much agree with you on that point, but this isn’t linked to high temperature.

@JamesPa, I wrote the original text and did the original analysis to show that high temperature heat pumps are not the panacea they are portrayed to be by the industry. I have no vested interests other than trying to make sure people are not hoodwinked in to fuel poverty. They are like supercars, they can go way above the speed limit, but there may be serious consequences not mentioned by the industry. The article was warning about the consequences and to show that they are quite competent low temperature machines in the right hands.

You only need a cop of 2.5 to make better use of the gas by burning it in a ccgt and using the electricity to run a heat pump, than piping and burning the gas at point of use.

Something to consider…

I have direct experience of this. When a high temp pump was put in to replace a low temp one in my rented accommodation running costs significantly increased no matter what was tweaked on it. It was a nightmare. There was no reason to replace it with the high temp one as the property was designed for a heatpump (except for the microbore).