Your fridge has one, your freezer might have two and your heat pump definitely has one: a compressor. It’s the refrigerant pump responsible for moving refrigerant around your system.

It lives in nearly ideal conditions: surrounded by warm oil, with no air or combustibles, so it never needs an oil change or any servicing.

If you sit quietly in your kitchen tonight, you’ll hear your fridge buzzing… that’s the compressor spinning. It sounds a bit like an electric razor or a rampant rabbit (Google it), but quieter.

If you listen to your heat pump, though, it’s unlikely you’ll hear a thing because the compressor is surrounded by layers of soundproofing.

They’re always black and the compressor lives inside the heat pump wrapped in insulation, both for noise reduction and to stop heat escaping.

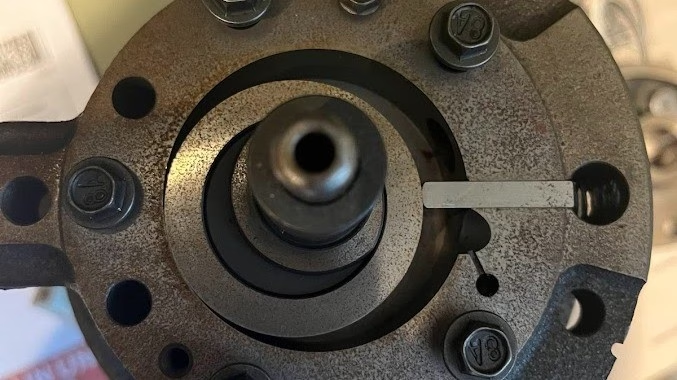

Inside, it’s a motor with a compressor module bolted on (see top picture). In all but the most dreadful heat pumps, the compressor motor is driven by an inverter, a clever device that controls the compressor’s speed: fast when lots of heat is needed, slow when it isn’t.

In the dark ages, we had fixed-speed compressors like those in your fridge. The first inverter air conditioners appeared in 1986, but the heat pump world was a bit slow to catch on. Some truly awful heat pumps still use fixed-speed compressors and I assume the developers of those go to work by steam train. I’ve never sold a heat pump with a fixed-speed compressor.

I wanted some real-world running data, so I went to the best in the business (Adia and Heatio) both of whom constantly log detailed operational stats. I asked for minute-by-minute data from a couple of random units.

The first example was a heat pump handling both heating and hot water, slightly oversized, which made it interesting. The compressor only runs when warm water is needed, so in summer it’s mostly off (except for hot water) and in winter it spins almost constantly. Over the year we analysed, it spent 62% of its time idle and only 436 minutes between 80-100% output.

Across that year, it turned 269.5 million times at an average of 450 rpm or about 7.5 revolutions per second if it had run 24/7.

In the second example, which was better sized, it spent 67% of the year idle and turned 237 million times in total.

A heat pump is expected to last 10-15 years. Based on these two examples, that’s roughly 3.5 billion rotations.

To put that in perspective: your car, doing 100,000 miles at an average 30 mph (around 3,000 hours at 2,000 rpm), achieves fewer than 500 million rotations.

You have to admit, a heat pump compressor is one seriously impressive piece of engineering.